photo by Pedro Ribeiro Simões

The New Puritan Generation

edited by José Francisco Fernández

*

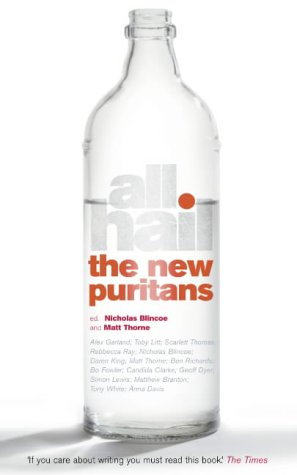

In the year 2000, two young editors, Nicholas Blincoe and Matt Thorne, published All Hail the New Puritans, an anthology of short stories which created an impact in what was considered a solid and consolidated cultural environment: the literary scene of Britain at the turn of the millennium. The collection reacted against a certain sense of complacency as regards the state of British fiction, usually viewed at the time as richly inventive, vigorous and plural. The fifteen writers included in the anthology (Scarlett Thomas, Alex Garland, Ben Richards, Nicholas Blincoe, Candida Clark, Daren King, Geoff Dyer, Matt Thorne, Anna Davis, Bo Fowler, Matthew Branton, Simon Lewis, Tony White, Toby Litt and Rebbecca Ray) represented the irruption of a new kind of writing, heavily based on genre and unashamed of its popular culture credentials. The stories themselves, together with the editors’ manisfesto, offered a new and stimulating approach to fiction, although the whole project had an outrageous reception by the literary establishment.

For the first time, a collection of essays addresses the importance of the New Puritan movement and provides guidelines to understand this generation of writers. The New Puritan Generation.

~

Download and read the full

Introduction to The New Puritan Generation

© José Francisco Fernández

~

ONLINE EXTRACT

from the Introduction to The New Puritan Generation

*

An elusive literary generation

This, in broad terms, is the breeding ground which favoured the publication of the anthology of short stories All Hail the New Puritans (2000), edited by Nicholas Blincoe and Matt Thorne, chosen here as the representative collection of a whole style of writing and a particular moment in English literature. The act of defining a generation is fraught with perils, particularly in this case when all of those who took part in it characteristically disavowed the whole enterprise somehow or other. When asked about the collection years after its publication, most of the writers dismissed their contribution to it, denying being part of a group and playing down its importance as something episodic, circumstantial and inconsequential:

I think the general consensus on the New Puritans is that we were all a load of wankers with an over-inflated sense of what we were doing. If I hadn’t been part of it, perhaps I would have thought that too — after all, I’m not sure we put across what we were trying to do in the most diplomatic way. But I can’t resist a manifesto, and it was a good idea … But being referred to as “New Puritan, Scarlett Thomas” does wind me up. As they say, you shag one sheep… Anyway, it was years ago and it was an experiment.

(Scarlett Thomas cited in Purbright, 2005)

Curiously enough, their transitory gathering together for the book made them typical of the prevalent attitude of the times; their indifferent, casual approach to the whole affair was what marked them as members of a contradictory, ephemeral but nevertheless distinguishable literary movement. Four women and eleven men, most of them born in England, contributed to the collection: Scarlett Thomas, Alex Garland, Ben Richards, Nicholas Blincoe, Candida Clark, Daren King, Geoff Dyer, Matt Thorne, Anna Davis, Bo Fowler, Matthew Branton, Simon Lewis, Tony White,  Toby Litt and Rebbecca Ray. At the time of the publication of the book they were in their late twenties and early thirties, and most of them had already published a couple of novels. Geoff Dyer was the eldest, 42, and the most experienced writer of the group – his first novel, The Colour of Memory, went back to 1989.

Toby Litt and Rebbecca Ray. At the time of the publication of the book they were in their late twenties and early thirties, and most of them had already published a couple of novels. Geoff Dyer was the eldest, 42, and the most experienced writer of the group – his first novel, The Colour of Memory, went back to 1989.

The claim for the participants in All Hail… to be grouped as a literary generation needs further consideration. They certainly shared some of the above-mentioned attitudes common to anti-establishment writers: they were commercially focused, colloquial-language adepts, furiously contemporary and, above all, willing to take part in a playful and stimulating adventure like writing a story for a book with a manifesto stated from the outset. In any case, a generous amount of artistic licence can be taken if one belongs to the vanguard of a literary movement, and tools like a manifesto can later be disowned if need be. The manifesto, furthermore, can be interpreted both as a question of nailing their colours and as a gesture in itself, a mark of their existence.

When the book was launched, they were met with a storm of criticism and the problem of the harsh antagonism that they found was that the critics took the initiative at face value, not realising that it was in part a strategic move by two intelligent editors in order to find an outlet for a good idea: they had wrapped themselves up in a movement to accompany the publication of a book of short stories. Among their many contrasting features, it must be said that the movement was very much a virtual one; no press conference was announced to issue a declaration, no final document was passed around for the participants to sign, but it is nevertheless true that the contributors enjoyed doing what they were asked to do. Their atypical features can be best exemplified if the concept of a founder is applied here: any literary movement has a leader, someone who clearly imagines the future and designs its ideology. But the symbol of a founding figure is not perhaps appropriate in a group of people who belonged to the same cultural milieu and drew on the same temper. Besides, editors Nicholas Blincoe and Matt Thorne were also contributors to the volume with one story each. Like the writers whose stories they commissioned, they were at the beginning of their literary careers too. Apart from that, the spirit of the experiment was very much equalitarian: ‘Fifteen writers; ten rules’ (Blincoe and Thorne, 2001: vii).

As radical young writers, they considered themselves

at the forefront of literary experimentation and as a

demonstrative gesture that they had arrived, a ten-point

declaration was boldly printed on the first page of the book.

If the New Puritans can be compared with a canonical literary generation, that is, any of the families of the poetic avant-garde in the first decades of the twentieth century, there are grounds to claim their belonging to a group, diffuse though it may be, diffuse as all groups are. As radical young writers, they considered themselves at the forefront of literary experimentation and as a demonstrative gesture that they had arrived, a  ten-point declaration was boldly printed on the first page of the book. This would count as the birth of any movement in classical terms: ‘In the case of groups that intend to be considered avant-garde, this process often involves a joint declaration of purpose or manifesto that identifies members and enemies’ (Strong, 1997: 7).

ten-point declaration was boldly printed on the first page of the book. This would count as the birth of any movement in classical terms: ‘In the case of groups that intend to be considered avant-garde, this process often involves a joint declaration of purpose or manifesto that identifies members and enemies’ (Strong, 1997: 7).

The New Puritan manifesto, later to be discussed in detail, was not the product of a joint discussion of the participants in the collection of short stories; it was solely conceived and written by the two editors of the collection, Nicholas Blincoe and Matt Thorne. But then all the writers they had approached sensed that it meant something new and not distant from their creative interests. Besides, they surely understood that it provided them with a trampoline for public recognition. As Beret E. Strong argues, ‘participation in a group empowers poets most when they are trying to make a name for themselves’ (1997: 8), and he adds: ‘As a tool that helps recently launched writers become known, the avant-garde group is useful for a limited time only and is then often dismantled as systematically as it was created’ (1997: 8). According to this authoritative opinion, the New Puritans could be considered a literary movement even if their members had only gathered for this particular occasion and if the movement had later to be disowned.

The writers of the collection had been chosen because for the editors they shared certain ‘modern’ requirements. They were the representatives in British fiction of ‘an international turn away from a baroque literary sensibility to something cooler and essentially prose- and narrative-driven’ (Blincoe, 2011). Nicholas Blincoe and Matt Thorne perceived that there was a new style struggling for recognition; recent experiments in alternative fiction (Children of Albion Rovers, 1996; Disco Biscuits, 1997; britpulp!, 1999) had proved successful. Blincoe and Thorne were part of that environment and they were well-connected. They simply presented in one bold move what was already there in a dispersed way: fiction which addressed the quotidian in a prosaic way, as if following a call to arms by the captain of disaffected suburban youth, Morrissey, when he had sung a few years before that the music played by the DJ no longer had the power to express the sense of his reality. They felt that a new vocabulary had to be invented.

~

The making of the book

The actual process of edition of the book was as follows: early in 1999 Nicholas Blincoe came up with the idea of translating into fiction what had been successfully made on film by Danish director Lars Von Trier and his Dogme 95 project. Von Trier had envisaged a new kind of film production in which all unnecessary elements were reduced to a minimum. The basic idea was to record the work of actors set in the present and in real locations, without recourse to special effects, additional lightning or music. In 1995 he and his colleague Thomas Vinterberg developed the ten rules of what they termed ‘The Vow of Chastity’, or the foundation of the new movement. All of these rules reinforced the idea of austerity in film making and by the end of the decade several productions, including the much acclaimed Festen, Jury Prize in Cannes Film Festival in 1998, were made following the trend initiated by Von Trier.

It was meant to be not only prescriptive,

but also encouraging, that is, it was meant to promote

the kind of narrative that they admired…

*

Nicholas Blincoe talked to his friend Matt Thorne about the project and they decided to go ahead with it. The title for the book was Blincoe’s idea, taking the cue from a ballet by Michael Clark he had recently seen: Hail the New Puritan had been a collaboration of Clark with post-punk group The Fall, and Blincoe liked it for its iconoclastic attitude. The starting point was the writing of the manifesto itself. There was something imposing, continental, authentic, reminiscent of the surrealist movements of the 1920s and 1930s in the drafting of a manifesto. In the case of Blincoe and Thorne’s, it was meant to be not only prescriptive, but also encouraging, that is, it was meant to promote the kind of narrative that they admired: ‘The initial concept was to come up with a list of restrictions (à la Dogme Vow of Chastity), but as we thought about it, we decided that the list would be a combination of qualities we recognized in the fiction we liked by contemporary writers and deliberate restrictions’ (Thorne, 2011).

The editors then drafted a list of anti-formalist rules that fulfilled different functions: they set the standard for the stories in the anthology, they expressed their reaction against the previous generation of ‘literary’ writers (in the subsequent discussion after the manifesto, Time’s Arrow by Martin Amis and Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie, were mentioned as the kind of literature they reacted against) and by this set of rules they announced to the world the official birth of the new sensibility:

THE NEW PURITAN MANIFESTO

1.- Primary story-tellers, we are dedicated to the narrative form.

2.- We are prose writers and recognise that prose is the dominant form of expression. For this reason we shun poetry and poetic licence in all its forms.

3.- While acknowledging the value of genre fiction, whether classical or modern, we will always move towards new openings, rupturing existing genre expectations.

4.- We believe in textual simplicity and vow to avoid all devices of voice: rhetoric, authorial asides.

5.- In the name of clarity, we recognise the importance of temporal linearity and eschew flashbacks, dual temporal narratives and foreshadowing.

6.- We believe in grammatical purity and avoid any elaborate punctuation.

7.- We recognise that published works are also historical documents. As fragments of our time, all our texts are dated and set in the present day. All products, places, artists and objects named are real.

8.- As faithful representations of the present, our texts will avoid all improbable or unknowable speculation about the past or the future.

9.- We are moralists, so all texts feature a recognisable ethical reality.

10.- Nevertheless, our aim is integrity of expression, above and beyond any commitment to form.

The spirit of the whole enterprise was both serious (some rules had to be obeyed) but also playful (it was fun to experiment with writing, to play the game). The ten rules certainly curtailed the writers’ freedom of choice, but it was liberating at the same time to tell a story pure and simple. In any case, it was obvious that the participants would take the manifesto as a guide, not as an inflexible set of commandments:

The manifesto was the point but should never be taken too serious. It could be interpreted on a number of levels – as a literary clarion call, as well as a very strong publicity bomb to throw amongst the critics. It raised some interesting ideas about fiction; it was also interesting to parallel fiction with the DOGME film discipline. But in the end, none of the writers took it particularly seriously and broke the rules at will. (Hollis, 2011)

When the book was published in September 2000, one of the most remarked-upon features of the anthology was that the stories covered more ground than was initially outlined: ‘Even at the time,’ novelist Richard Beard remembered, ‘I felt the manifesto didn’t match the contents of the book. The stories in the book are far more varied in style than the manifesto declares so stridently they ought to be’ (Beard, 2011).

But going back to the initial stages of the book, once the manifesto was written and revised (a technical restriction, for instance, urging contributors to write two rough drafts and a polish, was dropped), the idea for the book was sent to different publishing companies. It was actually very well received, with seven major publishers bidding on the rights. Blincoe and Thorne finally accepted the offer of Fourth Estate. The idea of the manifesto was thought to be good for advertising, it was timely and at the publishing house they found that the collection would enhance British fiction in their catalogue, which they felt was underrepresented. Surely the benefits in terms of cohesion provided by the initial ten rules did not go unnoticed to the publishers, as Paul March-Russell states: ‘The manifesto, then, overtly demonstrates how anthologies attempt to bind individual short stories to an overall purpose and identity’ (2009: 63).

For Blincoe, it was important to bring to life

intelligent, beautiful stories without excessive intervention.

Here the name of Leo Hollis enters the stage. A young and dynamic editor at Fourth Estate, he already knew Blincoe and Thorne and reacted favourably to the list of potential contributors that accompanied the manifesto. Of the initial twelve names, two of them, Douglas Coupland and Haruki Murakami, declined the invitation (Murakami had originally sent a story which would have not been accepted anyway, because it broke some of the rules), and new names, this time all British, were added to the list as both of them, Blincoe and Thorne, read more work from recent young authors. Leo Hollis supervised the process but did not intervene until the end, when all the stories had gone through Blincoe and Thorne, and he did a general edit of the whole collection. He worked with the book as with any other publication, without taking into account the rules of the manifesto. Only a limited amount of editing was done on the stories, normally by the editors in collaboration with the writers themselves so that they fitted the set of rules. For Blincoe, it was important to bring to life intelligent, beautiful stories without excessive intervention. For Leo Hollis this was a point he disagreed with: ‘I felt that the stories could have been worked on far harder than they were in the end’ (Hollis, 2011).

Finally Blincoe and Thorne wrote the introduction to the collection, which took the form of a dialogue of the editors although, as Nicholas Blincoe admitted to me, the dialogue form with two voices was ‘slightly artificial. There was a process of joint editorship so nothing that is said, could be attributed to either one or the other with one hundred percent certainty’ (Blincoe, 2011).

The fictitious conversation between Blincoe and Thorne is full of enthusiasm for the new trend and makes a strong case for pure story-telling as the raison d’être of the anthology. The editors made sweeping statements that relegated all other forms of writing to the paper bin: ‘without narrative the most attractive constellations of words or the most carefully poised sentences are nothing but make-up on a corpse’ (Blincoe and Thorne, 2001: viii). But of course they had to be provocative, bold, embattled, as befits the crusading spirit of the leaders of a cultural revolution. Other examples of this attitude, which did not really match what was on offer, included:

‘Today, fiction should be focusing on the dominance of visual culture…’

‘Poetry is so different to prose, it has nothing to offer or to teach the prose writer’

‘It is impossible to write verse without turning life into artifice’

‘Flashbacks are a cheap trick’

But the introduction also offered fresh, thought-provoking and exciting ideas, particularly for young writers:

‘Narrative is essentially flexible, it is flexible at its very core. In the end, stories resist any attempt to categorise them’

‘The truth is not that fiction can be escapist, but that fiction embodies a desire for freedom’

‘The bond between writer and reader is one of contemporaries, of peers, not master and initiate’

‘[F]iction writers should at least be the ones who legislate what is and what is not fine writing’

The introduction to the book is savvy and smart, and maybe it played its part by generating such an angry response in some quarters. Statements like ‘British fiction is currently among the most exciting in the world’ (vii) or the anthology being ‘a chance to blow the dinosaurs out of the water’ (vii) sound too ambitious for just a collection of short stories, and it was bound to meet a negative reaction. As Nicholas Blincoe admitted many years later: ‘We tend to pontificate and also to leap off from each rule to make wider social comments. Maybe we could have focused more on the key idea: what is prose fiction? Why does it work? And what makes it beautiful?’ (Blincoe, 2011).

Continue reading the full

Introduction to The New Puritan Generation

(including the reception of the New Puritans,

the impact of the movement and the present study).

~

José Francisco Fernández is Senior Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Almería, Spain. He has published widely on the contemporary British short story, including articles in journals such as Journal of the Short Story in English, ZAA, AUMLA and Irish Studies in Europe. He was one of the contributors to The Facts on File Companion to the British Short Story (2007). He is co-editor of Contemporary Debates on the Short Story (Peter Lang, 2007) and he has recently edited A Day in the Life of a Smiling Woman: The Collected Stories, by Margaret Drabble (Penguin, 2011).

José Francisco Fernández is Senior Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Almería, Spain. He has published widely on the contemporary British short story, including articles in journals such as Journal of the Short Story in English, ZAA, AUMLA and Irish Studies in Europe. He was one of the contributors to The Facts on File Companion to the British Short Story (2007). He is co-editor of Contemporary Debates on the Short Story (Peter Lang, 2007) and he has recently edited A Day in the Life of a Smiling Woman: The Collected Stories, by Margaret Drabble (Penguin, 2011).

~

With many thanks to both the author and publisher, Gylphi Limited (Canterbury, UK), for granting us permission to reprint the Introduction to The New Puritan Generation.