photo by Benson Kua

by Renia Simmonds

George Lambor was not famous, but he wanted to be. His ambition was to be a writer, not a lawyer, like his father, or a maths teacher, like his grandfather. He had a love of ancient history and was going to write about that, and, at the age of twelve, he had already secured his place at Krakow University in Poland for when he was older.

All of his plans were destroyed when Germany invaded Poland on 1st September 1939. Lambor was on holiday with his cousins, having left his parents and siblings at home, when his aunts, Countess Zaluska and Tola Sidorowicz, made the decision to flee Poland, taking Lambor with them. He kept a journal of their travels through Europe and, from that moment on, he couldn’t stop writing.

In December 1940, the refugees took a ship from Portugal to Liverpool. They settled in Peebles, near Edinburgh, and a benevolent uncle paid for Lambor’s schooling. Later, he was accepted at Oxford to read Polish Law, yet, after waiting for three months for the course to begin, he found it had been discontinued. Lambor tried to be accepted for history or archaeology courses, but none were available, and so he began to take on a number of odd jobs. It was at this time that he met the girl who was to become his wife, Margaret Palliser.

The young lovers married in Edinburgh early in 1952 and Lambor soon found himself responsible for a growing family. Always aspiring to be a writer though, he continued taking odd jobs in warehouses or as a lumberjack, which allowed him time to write. He also edited the Bulletyn, a Polish-language paper in Edinburgh, to which he was a frequent contributor.

But it wasn’t until Lambor moved his family to the south of England that his hopes of publication came to fruition. Lambor constantly sent his work directly to editors of the various magazines and journals, and hoped for the best. In those days,  offering unsolicited pieces was quite the norm.

offering unsolicited pieces was quite the norm.

The first story he had published was ‘The Best-Ever Jumble Sale’. It appeared in Woman’s Realm in 1961, under the pen-name of Tom Thompson, one of only a few times Lambor used this name. He used the real names and ages of his children, though, when describing their exploits. The family in the story, and in real-life, lived over the road from the church hall which did a roaring trade in jumble sales. Having emptied the house of all the children’s rubbish, including his young daughter’s fourteen handbags, the fictional family prepared for a visit from their ‘perfect’ uncle with his ‘perfect’ wife and children (who didn’t exist in real life). Unfortunately, there was a ‘mammoth’ jumble sale that day, which resulted in all the children acquiring useless treasures, including a bed. The ‘perfect’ cousins started ‘screaming like a couple of pigs being slaughtered’ when their mother demanded they dispose of this trash. But they went home from the sale, trash and all.

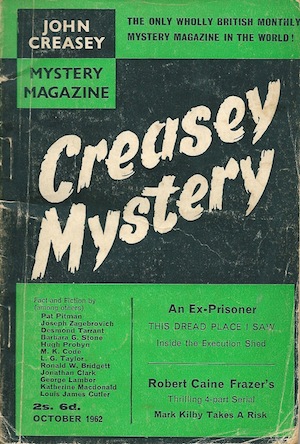

Lambor’s following stories were quite different. The first was a mystery about attempted murder, entitled ‘If Nina Could See Us Now’, published in Parade, and the second, ‘So Easy To Kill’, appeared in the John Creasey Mystery Magazine, which was presented as a book of thriller short stories.

The next of Lambor’s published short stories was ‘Chinese Junk’ and, like many of his tales, it was translated and published in several countries around the world. It was inspired by his daughter’s exploits in imitating the adventures of Nancy Blackett, from Swallows and Amazons. In real life, his daughter had taken to sailing a yacht on the Hove Lagoon, and she was utterly horrified when her aspiring author of a father ran it aground. Pirates, of course, do not run aground. In the story, a schoolboy runs aground in the South China Sea, the local lake. Out of necessity, he has to start smuggling to rectify someone else’s mistake. This story cleverly combined the world of the imaginative child with that of crime.

During this time, Lambor also wrote feature articles, one of which appeared in Weekend magazine. The piece was entitled ‘They Just WON’T Let You Wash the Dishes: What has happened to the good old days when a stint paid for your champagne?’ In a similar vein to his stories, the piece was filled with creativity and drew on his real life – namely his time as a student in the 1940s, when he sometimes offered to wash dishes in exchange for a meal:

A waiter is standing over you with the bill. Your girl-friend has been ordering all the expensive dishes. And now you find that you have left your wallet at home.

Antoinette Rose, the editor of Woman’s Realm, liked Lambor’s writing style and persuaded him to write many more stories for the magazine, including his highly successful piece ‘When in Paris’, which was based on his wife’s dream to go to Paris to paint in Place du Tertre. For a few years, Rose and Lambor had a good working relationship and she admired the way he wrote “with a Polish accent”, as she put it, giving him a distinctive style. But in 1966, this relationship ended. The magazine stopped accepting his stories and, at the same time, Rose got married. This could have been a coincidence, or it could have signalled the dawn of a new fiction editor. The last of Lambor’s stories to be published in Woman’s Realm was ‘The Vase of Ta Chin’. It was about two ladies contemplating the value of a family heirloom and whether it should be sold to raise money.

Antoinette Rose, the editor of Woman’s Realm, liked Lambor’s writing style and persuaded him to write many more stories for the magazine, including his highly successful piece ‘When in Paris’, which was based on his wife’s dream to go to Paris to paint in Place du Tertre. For a few years, Rose and Lambor had a good working relationship and she admired the way he wrote “with a Polish accent”, as she put it, giving him a distinctive style. But in 1966, this relationship ended. The magazine stopped accepting his stories and, at the same time, Rose got married. This could have been a coincidence, or it could have signalled the dawn of a new fiction editor. The last of Lambor’s stories to be published in Woman’s Realm was ‘The Vase of Ta Chin’. It was about two ladies contemplating the value of a family heirloom and whether it should be sold to raise money.

After this, Lambor had just one further success with the short story. In April 1968, ‘My Favourite Lobster’ was read out on BBC Radio’s Morning Story, by Maurice Denham:

“You can leave that till after tea,” grandmother said. “It’s nearly ready. And do you know what?” She twigged my nose. “I have your favourite: a lobster!”

From the sound of her voice I could see she was doing me a favour. But, my favourite was a chocolate mousse. Lobster, I had never heard of. So when she left the room, puzzled, I asked grandfather what a lobster was.

“Well, now.” He sat down in an armchair and put me on his knee, which at least gave me a chance to touch his beard. “It’s a sort of creepy-crawly. An odd-looking customer, but I love it.”

“Do I love it, grandfather?”

‘My Favourite Lobster’ was an extract from a longer story he had written in October 1961, titled ‘Go Home, Andrew!’ It was about a boy who stayed with his grandparents while his mother had a new baby. In this version, Andrew hated being with his grandparents and resolved to run away and go back to school to make an Easter egg. However, in the broadcast version, the theme was not about running away, but about the fear and love of a little boy for his mischievous grandfather.

‘My Favourite Lobster’ was an extract from a longer story he had written in October 1961, titled ‘Go Home, Andrew!’ It was about a boy who stayed with his grandparents while his mother had a new baby. In this version, Andrew hated being with his grandparents and resolved to run away and go back to school to make an Easter egg. However, in the broadcast version, the theme was not about running away, but about the fear and love of a little boy for his mischievous grandfather.

Editors compared Lambor’s work with that of another Polish author, Joseph Conrad. But for every short story he had published, Lambor’s archive contains two or three more which were rejected or abandoned. He also wrote two novels which were never published, To Catch a Plane and Sitka Poison.

Sadly, the ambling world of the post-war period was well and truly over and people’s expectations and hopes became more complex, and more commercial. Lambor’s easy-going stories of family life, hopes and dreams, and imaginative children were no longer fashionable. By the late 1960s, the world had changed and the teenager was now the dictator of trends. Women’s magazines, such as Woman’s Realm, increasingly had to compete with new publications, including the sexy Cosmopolitan, or 19, which favoured the work of Jilly Cooper and Jeremy Clarkson. Editors were on the look-out for fiction with bite that appealed to these new, trendy, young consumers.

Some of these new, young consumers fancied trying their hand at writing themselves. Lambor took advantage of this and, for almost ten years, taught a popular course – Writing For Pleasure and Profit – at a couple of local colleges, while working full-time at a local hotel, though this left him little time for his own creative writing.

By the 1970s, Lambor’s first love of ancient history was beginning to take precedence, particularly in his study of Ossian, the bard at the core of James Macpherson’s epic poems. He began writing pieces for Popular Archaeology, amongst other publications. He inherited some money, from his Aunt Tola, and used it to renovate the old family house, in Wojnicz, to turn it into a museum. He also began to deal in antiquities. In 1986, he founded his own magazine, Ancient. The magazine was produced until his death in 1997, at which time it had broken the American market and was due to emerge in Australia. Lambor wrote many of the articles himself under various names, including Tom Thompson.

~

George Lambor’s obituary appeared in The Independent on 26th June 1997.