photo © Jason Ballard, 2015

by Mike Smith

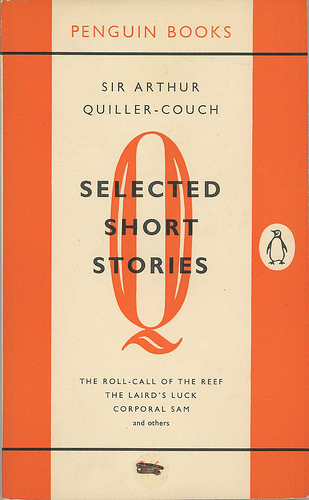

I had heard of Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch – known simply as ‘Q’ to his readers – but had not read much by him until I was given the Penguin Selected Short Stories, from 1957, in which ‘A Cottage in Troy’ appears. He won public honours and lectured at Cambridge, and was one of the team that put together Hammerton’s twenty-volume collection, The World’s Thousand Best Short Stories, in 1904. He also provided the introductory essays, which, I recall, are often as remarkable for their obvious enthusiasm and enjoyment of the form, as for their not inconsiderable erudition. It is a shame, then, he did not make it into Volume II of Philip Hensher’s Penguin Book of the British Short Story, last year. Nor did he make it into the doorstop 1994 Reference Guide to Short Fiction. Three of his stories are in the Hammerton Best Thousand collection, but ‘A Cottage in Troy’ isn’t among them.

This is a curious story. The structure notably presents it as two quite disconnected stories; the only obvious connections between them are the author and his narrative proxy, and the fact that both are written as if seen from the perspective of the eponymous cottage. Numbered I and II, both have titles of their own. The first, ‘A Happy Voyage’, has the first person narrator spend an evening on a ship in the town’s harbour, listening to the voice, and dancing to the fiddle, of his ex-housekeeper’s new husband. The housekeeper and her husband have boarded the unused vessel to have a secret honeymoon, and to escape from their everyday personas. Spotted from the shore by the narrator – who has already bewailed to us the loss of his servant, and her abilities with an omelette – they invite him to join them, and he rows out to the moored ship. Until sunrise they share with him the last night of their week-long adventure. Then they return, as he witnesses for us, to their previous, mundane lives: ‘It was half farce, half deadly earnest.’

This is a curious story. The structure notably presents it as two quite disconnected stories; the only obvious connections between them are the author and his narrative proxy, and the fact that both are written as if seen from the perspective of the eponymous cottage. Numbered I and II, both have titles of their own. The first, ‘A Happy Voyage’, has the first person narrator spend an evening on a ship in the town’s harbour, listening to the voice, and dancing to the fiddle, of his ex-housekeeper’s new husband. The housekeeper and her husband have boarded the unused vessel to have a secret honeymoon, and to escape from their everyday personas. Spotted from the shore by the narrator – who has already bewailed to us the loss of his servant, and her abilities with an omelette – they invite him to join them, and he rows out to the moored ship. Until sunrise they share with him the last night of their week-long adventure. Then they return, as he witnesses for us, to their previous, mundane lives: ‘It was half farce, half deadly earnest.’

The event has been absurd – she dressed out of her class, as a lady; he out of his accustomed philosophy that ‘life’s a dull pilgrimage to a better world’ – but the narrator cannot banish the memory from his mind. Neither can he bring himself to mention it again to either of them. It is a haunting tale, for we too, perhaps, will find it memorable, not least because it poses questions that it does not answer.

The second story, ‘These an’ That’s Wife’, is centred on the ferry that takes Tom Warne (aka These an’ That) across the river to town. His story, of being abused and disregarded by his gypsy wife and her gamekeeper lover, is discussed, in his presence, by his neighbours on the ferry. The poor husband not only fails to defend himself, but begs his neighbours not to raise the issue. They, however, choose to fight his corner for him, and treat the errant wife to ‘rough music’, though Quiller-Couch uses the term ‘Ramriding’. At the end of the ride, the wife is ducked, but the ducking stool breaks and she appears to drown. Only then does the worm turn, and the husband wishes that the crowd had subjected the gamekeeper to the treatment. ‘“Naybours,” the words came at last, in the old dull tone; “I’d as lief you hadn’ thought o’ this.”’

He carries his unconscious wife home, where she recovers to elope the following week with her lover. And, once again, a question is raised – that of how we feel about the protagonist’s attitude and behaviour – but not answered for us.

The narrative voice is simple and straightforward – and not the same one as used by Quiller-Couch in other stories, such as those narrated by Gabriel Foot, a Highwayman. Instead, the narrator in ‘A Cottage in Troy’ has allowed the characters to speak in their own voices too. For stories written a hundred years ago,  the language can be unexpectedly accessible:

the language can be unexpectedly accessible:

‘The cottage that I have inhabited these six years looks down on the one quiet creek in a harbour full of business.’

~ the opening of ‘A Happy Voyage’

‘In the matter of These-an’-That himself, public opinion in Troy is divided.’

~ the opening of ‘These-An’-That’s Wife’

The narrator in the two stories is the same, we might imagine – though that is not explicitly stated – and it is his tone of voice, his incomprehension perhaps, the implication that he must reflect upon the stories he has told us, that forges another subtler connection between the two than the mere accident of their location.

I cannot help pondering if Quiller-Couch conceived the two stories that make up ‘A Cottage in Troy’ as a pair. They are both quite short stories and I wonder if, at the time of first publication, cited as 1891, there was a reluctance to publish such short pieces as single items – for fear of dismissal as mere ‘anecdote’. There’s an argument yet to be made, I feel, in favour of the anecdote as the lynch-pin of all fiction, but it could be that there was a less mundane reason for pairing these two stories. From my own experience, I know that stories can resonate with others written months or even years before. The interest, for me, at least, in this pair from Quiller-Couch is that they are so different in content, yet so similar in tone of voice, which makes them a pairing of ‘form’ rather than ‘content’; perhaps a ‘writerly’, rather than a ‘readerly’, pair.

~

Mike Smith writes across a range of genres, including poetry, drama, and literary criticism. Under the name Brindley Hallam Dennis he has published That’s What Ya Get! Kowalski’s Assertions (Unbound Press, 2010), the novella A Penny Spitfire (Pewter Rose 2011), and, in 2012, Talking To Owls (Pewter Rose), a collection of short stories, monologues and flash fictions. In 2009, he received the degree of MLitt from Glasgow University. He currently teaches Creative Writing at Cumbria University. His writing has been published, broadcast and performed, and has won prizes and awards in Scotland and England. He is particularly interested in the structure of short stories, and in the relationship between the story and the narrator. He is keen on the ‘told’ story, and some of his tellings can be found at BHDandMe on Vimeo. He has a collection of essays on short story form due out from Pewter Rose Press, and a collection of short stories from Sentinel Publications. He is a founder/presenter of LitCaff, a monthly evening of fiction (with added poetry) in Carlisle, England. His most recent collection of short stories is The Man Who Found A Barrel Full of Beer, written as Brindley Hallam Dennis. His collection of essays on A. E. Coppard, English of the English, features responses to the tales of A. E. Coppard.

Mike Smith writes across a range of genres, including poetry, drama, and literary criticism. Under the name Brindley Hallam Dennis he has published That’s What Ya Get! Kowalski’s Assertions (Unbound Press, 2010), the novella A Penny Spitfire (Pewter Rose 2011), and, in 2012, Talking To Owls (Pewter Rose), a collection of short stories, monologues and flash fictions. In 2009, he received the degree of MLitt from Glasgow University. He currently teaches Creative Writing at Cumbria University. His writing has been published, broadcast and performed, and has won prizes and awards in Scotland and England. He is particularly interested in the structure of short stories, and in the relationship between the story and the narrator. He is keen on the ‘told’ story, and some of his tellings can be found at BHDandMe on Vimeo. He has a collection of essays on short story form due out from Pewter Rose Press, and a collection of short stories from Sentinel Publications. He is a founder/presenter of LitCaff, a monthly evening of fiction (with added poetry) in Carlisle, England. His most recent collection of short stories is The Man Who Found A Barrel Full of Beer, written as Brindley Hallam Dennis. His collection of essays on A. E. Coppard, English of the English, features responses to the tales of A. E. Coppard.