('Library At Orchard' © Benjamin Ho, 2016)

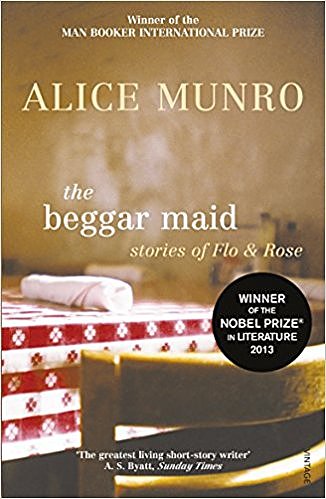

THE BEGGAR MAID: A NOVEL MADE MINIATURE

by EMILY DEVANE

Alice Munro’s short story ‘The Beggar Maid’ buttonholes the reader from the start: ‘Patrick Blatchford was in love with Rose.’ It’s a great opening line, taking us right into the heart of the story about a couple who meet at university. From there, Munro quickly reveals the central problem: theirs is a relationship based on deceit. Rose is poor and spiteful – but clever and resourceful, and Patrick’s love promises to lift her from her humble origins. He, meanwhile, is rich and high-minded – but also snobbish and weak-willed. His choice of Rose is confusing: he loves her and yet he wants to change her. Most remarkable, though, is the scope of the story, which takes us from the couple’s first meeting to a chance encounter many years later. Munro achieves novel-like resonance in short story form. It is a masterclass of technique.

In the first paragraph, we learn that Patrick disapproves of Rose’s friend Nancy, with whom she eats hot fudge sundaes and shops for ‘tarty silver sandals’, all because Nancy can’t pronounce ‘Metternich’. What’s more, Rose cannot defend this friendship and has to hide this non-intellectual side of herself from Patrick. As readers, we are complicit in her deception, and are as horrified as we are intrigued by their unfolding relationship.

The central lie of the story is in its title. Patrick, a graduate student with ambitions to become a history professor, gushingly calls Rose his ‘Beggar Maid’, casting her as the poor but beautiful Penelophon who ‘loses all trace of her former poverty and low class’ when she is rescued by King Cophetua. But Rose is no subservient maid – she rails against the other scholarship girls with scaly patches on their cheeks, hair in maidenly rolls, and sweat-stained clothing. And Patrick is also no Cophetua. For that, Rose laments, he’d have to be ‘sharp and swarthy, clever and barbaric.’ Ironically, in this Pygmalion-esque fantasy, she is far cleverer than he.

The central lie of the story is in its title. Patrick, a graduate student with ambitions to become a history professor, gushingly calls Rose his ‘Beggar Maid’, casting her as the poor but beautiful Penelophon who ‘loses all trace of her former poverty and low class’ when she is rescued by King Cophetua. But Rose is no subservient maid – she rails against the other scholarship girls with scaly patches on their cheeks, hair in maidenly rolls, and sweat-stained clothing. And Patrick is also no Cophetua. For that, Rose laments, he’d have to be ‘sharp and swarthy, clever and barbaric.’ Ironically, in this Pygmalion-esque fantasy, she is far cleverer than he.

Patrick is an awkward and unlikely hero, with his way of knocking things over ‘like a comedian’, his voice breaking when he is stressed ‘– with her, it seemed he was always under stress –’ and the birthmark ‘dribbling like a tear’ down his cheek. He tells her, apologetically, that the birthmark will have faded away by the time he is forty, as if reassuring her that he is a good, long-term bet.

The deceit that brings the couple together in the library is intriguing:

Once a man grabbed her bare leg, between her sock and her skirt.…She had seen a man crouched down looking at the books on a low shelf, further along. As she reached up to push a book into place he passed behind her. He bent and grabbed her leg, all in one smooth startling motion, and then was gone. She could feel for quite a while where his fingers had dug in. It didn’t seem to her a sexual touch; it was more like a joke, though not at all a friendly one.

Although it’s never explicitly stated, it’s obvious that Patrick – with his flushed skin and excitable voice – is behind the act. Later, when she brings up the incident in jest, Patrick’s inability to take the joke implicates him further. There’s an ambiguity here: a man who worships her and yet says spiteful things, grabs her ankle so tightly it hurts, disapproves of the company she keeps, and wants to change her. This initial deceit is never fully resolved and it sits between them throughout the story.

Rose has become acutely aware of her humble origins. She is repulsed by her hometown, Hanratty, never more so than when she takes Patrick home and sees it anew: poverty ‘wasn’t just deprivation. It meant having those ugly tube lights and being proud of them.’ We notice all the inelegant details along with Rose: the plastic swan napkin holder (the attempt at class so woefully misjudged on stepmother Flo’s part), the malicious gossip, the talk of money, the bathroom noises, Billy Pope’s sausages. ‘It is a dump,’ Patrick concludes.

Conversely, Patrick’s family is snobbish, and at his palatial home on Vancouver Island Rose finds ‘a terrible amount of luxury and unease.’ Patrick’s mother is withdrawn, balking at emotion and ‘fanciful’ conversation: ‘Size was noticeable everywhere, from the thickness of towels… to silences.’ We get the distinct impression that Patrick has chosen Rose as an act of defiance. He parades her in front of his family, shows off about her academic accolades, and responds to his belligerent father in ‘an angry, pompous but nervously breaking voice.’ Rose knows his parents don’t approve of her and perversely, this seems to give Patrick satisfaction: ‘They don’t like you because I chose you,’ he says.

For Rose, choosing Patrick elevates her from her past – and yet she isn’t quite ready to let go: ‘Now that she was sure of getting away, a layer of loyalty and protectiveness was hardening around every memory she had…’ Rose doesn’t see at this point that the choice is not black and white. She does not wish to make a Penelophon-like transformation – and nor does she need to.

Throughout the story, Rose considers her options, wrongly assuming they are limited. Patrick wants her to be his ‘beggar maid,’ while Dr. Henshawe, the retired English professor with whom she boards, and who wants Rose as her protégé, disapproves of Patrick, and urges Rose to use her brain and reject the choices commonly open to women.

The two antagonists provide Rose with a choice: the life of an intellectual or of a married woman of means. In reality, neither of these choices suits Rose for what she really wants to is to be ‘known and envied, slim and clever’. Rose hankers for a life of glamour and fame, lamenting that among Dr. Henshawe’s scholarship girls ‘there were no actresses… no brassy magazine journalists.’ Like the sundaes with her friend Nancy and the food she privately devours in her bedroom, Rose’s secret desires remain just that. When Dr. Henshawe attempts to dissuade Rose from romance, telling her ‘Well, you are a scholar, you are not interested in that,’ it has the opposite effect, and in part, Rose chooses Patrick as an act of rebellion. Back in Hanratty, having agreed to marry Patrick, Rose is dismayed to find that ‘she dimpled and sparkled and turned herself into a fiancée with no trouble at all’.

Patrick, for all his talk of intellectualism and rebellion, is similarly fickle. He remains loyal to his moneyed roots, gives up his wish to become a historian ‘for her sake’ and agrees to join the family business:

It seemed that Patrick’s desire to marry, even to marry Rose, had been taken by his father as a sign of sanity. Great streaks of bounty were mixed in with all the ill will in that family. His father at once offered a job in one of the stores, offered to buy them a house. Patrick was as incapable of turning down this offer as Rose was of turning down Patrick’s, and his reasons were as little mercenary as hers.

In a rare moment of honesty, however, Rose tells Patrick she cannot marry him, and when he forces her to give him an explanation she finally admits the truth: ‘“I don’t love you!” she said. “I don’t love you. I don’t love you.” She fell on the bed and put her head in the pillow. “I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry. I can’t help it.”’ But, seeing him alone in his carrel at the library a few days later, she is full of remorse for the hateful things she said and is moved to take him back. It is another deceit though: Rose sees herself as bestowing on Patrick some ‘surprising bounty’ by restoring her love. In truth, she’s run out of options; she cannot think of another plan for herself. After the story jumps forward in time, she muses about her actions: if she’d had the price of a train ticket to Toronto, would things have been different?

In the final pages of the story, we learn that Rose did indeed marry Patrick and that they remained married a full decade before they divorced. The marriage itself is sketched out very quickly with the narrator describing the end of the marriage in a reflective tone:

during that time the scenes of the first breakup and reconciliation had been periodically repeated, with her saying again all the things she had said the first time, and the things she had held back, and many other things which occurred to her.

But, she also acknowledges, that there had been better times when:

happiness, the possibility of happiness, would surprise them. Then it was as if they were in different though identical-seeming skins, as if there existed a radiantly kind and innocent Rose and Patrick, hardly ever visible, in the shadow of their usual selves.

The final scene of the story takes place at Toronto Airport, with a chance encounter, nine years after they divorced. Rose sees Patrick from behind, but knows him at once. Her former feelings are rekindled and briefly, she considers attempting a repeat of the library scene that worked so well before:

…she had the same feeling that this was a person she was bound to, that by a certain magical yet possible trick, they could find and trust each other, and that to begin this all that she had to do was go up and touch him on the shoulder, surprise him with his happiness.

As he turns toward her, Rose sees that his ‘academic shabbiness’ and ‘his look of prim authoritarianism’ are gone. And just as he had predicted, the birthmark, too, has faded with time. One wonders whether Rose should have had more faith in him all those years before.

When Patrick sees Rose, however, his reaction is all the more startling and final. He wears a look of complete loathing: she no longer has the power to win him over.

Munro uses time famously well and upon finishing ‘The Beggar Maid’ we feel as if we have lived a lifetime – and all in the space of thirty or so pages. Time slows down for certain close-up scenes (in the snow outside Dr. Henshawe’s house; the trying dinner at Hanratty; the morning in which Rose tries to break off the engagement) and speeds up at others. In addition, rather than sticking to a linear narrative, the story lurches back and forth in time with characters introduced in passing only to be explained at a later point. It is as if someone is telling us a story in one big gushing torrent, with the bits we need to know added any which way. This use of time – of summary interspersed with moments of focus, of stories folded in on themselves – is how Munro achieves the novel-like feel in the space of a short story.

Being the story of a whole relationship, there is a completeness to ‘The Beggar Maid’ that is satisfying, even though it is no conventional love story. Munro does not supply us with a neat Hollywood ending. Rather, the story is purposefully disorienting at times, and what we get is something deeper and more illuminating – a story which mimics the messiness of real life. Our reader’s hunch that this relationship was set to fail from the off has been proved correct. Rose and Patrick are ambiguous to the end: we sympathise with them both, even though their flaws are achingly exposed. And yet there is something so beguiling about this couple, stumbling about in their quest for love, deluding themselves and each other. Few stories withstand re-reading: relish the ones, like this, that do.

‘The Beggar Maid’ can be found in Munro’s 2004 collection The Beggar Maid: stories of Flo and Rose.

~

Emily Devane lives and writes in Ilkley, West Yorkshire. Her short stories have been published in various anthologies and journals, including The Nottingham Review, The Lonely Crowd and Flash: The International Short-Short Story Magazine. A Word Factory Apprentice in 2016, she was mentored by Professor Ailsa Cox, who introduced her properly to the work of Alice Munro. Emily was given a Northern Writers’ Award in 2017 for her short story collection-in-progress. Her story ‘The Hand That Wields The Priest’ won the Bath Flash Fiction (February, 2017) and has since been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.