photo by Fergal Jennings

by Christine Genovese

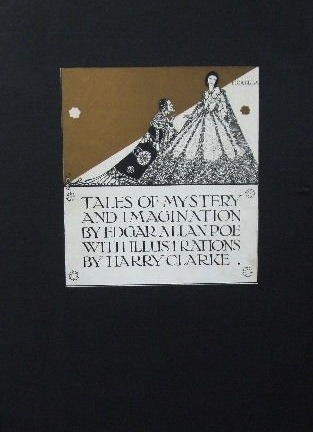

About thirty years ago I bought a copy of Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination in a second-hand bookshop. According to the pencilled-in price on the front endpaper, it cost me £6. On the verso of the title page is the following information: ‘First published in 1919: this edition © 1971 The Minerva Press Ltd.’

My copy is bound in blue cloth with gilt lettering and vignettes on the spine and front cover. It’s a hefty tome: 382 pages thick, weighing in at 1.25 kilograms.

The lay-out and the selection of stories and illustrations faithfully reproduce the George Harrap 1919 edition… the 1919 cloth-bound edition that is. There was also a limited, vellum-bound edition of 170, printed on hand-made paper and each signed by Harry Clarke, the illustrator. He contributed 24 full-page black and white drawings, plus several small end motifs. Such books cannot be reproduced… sadly, neither can they be picked up for a song in a second-hand book shop.

Harry Clarke was an outstanding Irish stained glass artist who also excelled as an illustrator of books, among them Hans Anderson’s Fairy Tales and Goethe’s Faust. He was influenced by the Art Nouveau style.

Harry Clarke was an outstanding Irish stained glass artist who also excelled as an illustrator of books, among them Hans Anderson’s Fairy Tales and Goethe’s Faust. He was influenced by the Art Nouveau style.

Poe’s stories have a black and white quality to them which is perfectly matched by Harry Clarke’s illustrations. In ‘Berenice’, the narrator explains that ‘Misery is manifold […] But as in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact, out of joy is sorrow born.’ The plates are predominantly black with striking white details. My guess is that the ratio of black to white in Harry Clarke’s artwork probably matches the ratio of sorrow to joy in the stories they illustrate. The frontispiece illustration, however, displays more white areas than any of the others. Its title is ‘Landor’s Cottage’ and it illustrates the book’s final story.

Anyone who embarks on that story with, say, ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ still lingering in their minds, might feel uneasy as the story unfolds. Poe rarely dwells on the perfect harmony between man and nature without conjuring up scenes of dread. And so they will mistrust the chocolate-box, bucolic idyll described in ‘Landor’s Cottage’. Yet the idyll remains unbroken.

Poe’s narrator found the cottage hemmed in by cliffs and rivers and isolated from the rest of the world like a vision of paradise, or Eldorado:

This lakelet was, perhaps, a hundred yards in diameter at its widest part. No crystal could be clearer than its waters. Its bottom, which could be distinctly seen, consisted altogether of pebbles brilliantly white. Its banks, of the emerald grass already described…

If we compare this pretty scenery to another stretch of water from ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, we get a strong sense of Poe’s skill with atmosphere:

I reined my horse to the precipitous brink of a black and lurid tarn that lay in unruffled lustre by the dwelling, and gazed down – but with a shudder even more thrilling than before – upon the remodelled and inverted images of the grey sedge, and the ghastly tree-stems, and the vacant and eye-like windows…

When Roderick Usher’s fragile mind finally gives in to the combined negative forces that have gradually undermined it, he and his entire house sink into this ill-omened tarn.

Harry Clarke’s illustration for ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ shows an open door with a narrow, white, vertical panel slicing through a solid black background. Lady Madeline appears in this opening, arms outstretched, tall and skeleton-like with ragged grave-clothes falling off her wasted body. She’s half ghost, half dying; caught in the macabre no-man’s-land that Poe frequently explored in his stories.

Clarke’s illustrations have a slow, almost static dignity. The characters are poised for movement, caught in a moment that fixes them in a deadlock. They are elongated, emaciated and are often drawn with a rectilinear element that stresses their static posture. The eyes are set deep in large, dark sockets that suggest an introverted mind.

Poe’s concept of time was abstract. In a piece titled ‘Time and Space’ (published in the Democratic Review in 1844), he questions the way painters line up objects of diminishing sizes to create a sense of space, and compares it with the way writers line up events to create a sense of time. He says the effect is ‘mere confusion of the two notions of abstract and comparative distance’.

‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ appears to describe a sequence of events. But the narrative is, in fact, a series of static tableaux in which the narrator’s fixation becomes increasingly sinister. ‘For a whole hour I did not move a muscle… just as I have done, night after night, hearkening to the death-watches in the wall.’

‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ appears to describe a sequence of events. But the narrative is, in fact, a series of static tableaux in which the narrator’s fixation becomes increasingly sinister. ‘For a whole hour I did not move a muscle… just as I have done, night after night, hearkening to the death-watches in the wall.’

The conclusion reiterates the theme of the nature of death, as the victim’s heartbeat exerts its mysterious power.

Clarke’s illustration shows the narrator perched on his victim’s bed, listening for the still-beating heart. The sound rises in swirling patterns from the dark bedding, which covers the old man and his eye. The narrator is like a bird of prey with a wing-like cape behind him and bulging eyes staring from deep sockets.

Poe never used the title Tales of Mystery and Imagination himself. In 1839, he published Tales of the Grotesque and the Arabesque. Harry Clarke’s illustrations go hand in glove with Poe’s own title.

Words like ‘grotesque’ and ‘arabesque’ are terms that no longer have quite the same connotations as they did for Poe or for Clarke. ‘Grotesque’ is an art term derived from the word ‘grotto’, or underground chambers, such as those discovered in Rome in the 16th century and in Pompeii in the 18th century. These chambers were decorated with strange, distorted patterns of intertwining plant, animal and human motifs, which date back to the 1st century AD.

Many observers found the unnatural aspect of the Italian grotto-esque art disturbing and macabre, and when literature displayed similar qualities they applied the same term. ‘Grotesque’ elements in literature are various. They are found, for example, in dystopian or speculative settings (e.g., Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels,); they are also vital to, for example, the bawdy and down-to-earth tales of Rabelais. As a dynamic within literature, the grotesque often challenges social norms and questions the power of fixed rational thought. At times, it marries itself to the Gothic and yields ominous atmospheres and ambiguous states – from darkness and mist to roaming demons. The terrain of the grotesque was familiar to both Poe and Clarke.

In Poe’s time, the word ‘Arab-esque’ was often synonymous with Arabia, and had particular associations with the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, translations of which appeared at the beginning of the 18th century. These tales became immensely popular and gave rise to a multitude of ‘oriental’ elements in art and literature. But the terminology can be slippery in the case of words like ‘arabesque’, ‘moresque’, ‘oriental’, ‘ottoman’, ‘Indian’, ‘Saracenic’ and the like. They’re often used to suggest an exotic atmosphere far removed from the Christian ethos, an atmosphere where demons and other spirits are not confined to one’s nightmares.

Poe mentions arabesques in several stories, including ‘Ligeia’ and ‘The Assignation’ where they heighten the atmosphere of dread. The arabesque pattern of the curtains and wall-hangings in ‘Ligeia’ appear at first like ‘simple monstrosities’, but as the visitor moves around the chamber, he is ‘surrounded by an endless succession of the ghastly forms.’ In ‘The Assignation’, the narrator’s friend declares that ‘Like these arabesque censers, my spirit is writhing in fire…’

Clarke makes extensive use of arabesques in his illustrations. Delicate leaves and stems decorate spaces everywhere. They are pretty – objectively speaking – but it’s clear that they are also threatening. They rise from the bottom of the page; they creep up the edges; they crowd in on the characters, allowing no breathing space, until the claustrophobic horror seems inescapable.

Clarke’s arabesques correspond closely to Poe’s. His illustration for ‘Morella’ has a surfeit of arabesques. The dead Morella lies in the lower part of the drawing and, above her, is the pensive face of the narrator, her husband. The rest of the page is teeming with a writhing throng of minuscule figures. Most of these are floral motifs, but rising from Morella’s chest is a swirl of grotesque figures; an endless succession of faces all endowed with Morella’s features.

In ‘Morella’, Poe explores one of his primary preoccupations: the transition from life into the beyond. He was attracted to the idea of something beautiful beyond death, but outside the Christian ethos. He dreaded the thought of death as an absolute end. The solution suggested in ‘Morella’ is a simple one: a person can live on in the next generation. When Morella dies, her daughter is born, and as the child grows we see that she is an exact replica of Morella – a clone. She takes on her mother’s appearance and gradually begins to speak and sing in the way her mother did, haunting her father. The effect is deeply unsettling.

In ‘Morella’, Poe explores one of his primary preoccupations: the transition from life into the beyond. He was attracted to the idea of something beautiful beyond death, but outside the Christian ethos. He dreaded the thought of death as an absolute end. The solution suggested in ‘Morella’ is a simple one: a person can live on in the next generation. When Morella dies, her daughter is born, and as the child grows we see that she is an exact replica of Morella – a clone. She takes on her mother’s appearance and gradually begins to speak and sing in the way her mother did, haunting her father. The effect is deeply unsettling.

Poe considered ‘Ligeia’ one of his best stories. Ligeia is determined to refuse death; she believes in the force of will-power. After her death, her husband sinks into an opium haze. He remarries but treats his new wife with contempt. Their chamber is crowded with luxurious, oriental furnishings that create a claustrophobic atmosphere of decadence.

The death of the second wife seems the logical outcome. Poe tightens the atmosphere to an unbearable pitch, at which point the story seemingly cannot proceed any further. But remember that Ligeia has refused to die and now, her spirit takes over the newly vacated body. When the ‘ghastly cerements’ fall away, Ligeia is resurrected.

Clarke’s illustration for ‘Ligeia’ shows the narrator prostrate in devout adoration of the eponymous heroine. Ligeia stands proud and statuesque, with a halo-like decoration around her head. The lower part of the plate is teeming with arabesque patterns crawling up the two figures. Their eyes are dark sunken shadows.

Poe had a strong sense of humour, in spite of his morbid fixation on death. In ‘The Premature Burial’, the narrator explains his own phobia by citing numerous authenticated examples of people who have been buried alive. He goes to obsessive lengths to construct a grave with an escape route. Nevertheless he wakes up in what seems to be a common grave and he panics. It becomes apparent that he’s slept on a narrow bunk bed on board a sloop. From that moment he ceases his ‘charnel apprehensions’ and stops reading ‘bugaboo tales – such as this.’

Clarke’s illustration for the story is almost entirely black. Inside a coffin buried deep in the ground, with grotesque shapes above and below, is the horrified face of the narrator. The accompanying quotation is: ‘Deep, deep, and for ever, into some ordinary and nameless grave.’

My copy of Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination illustrated by Harry Clarke is not a prestigious collector’s item. Its value is an aesthetic one: the combined talents of two great artists in one volume to be enjoyed again and again.