('Caerphilly Panorama' © nzbuu, 2009)

*

SMALL TOWN GLORY

by SOPHIA KIER-BYFIELD

~

So, where are you a local? I propose a three-step test. I call these the three “R’s”: rituals, relationships, restrictions.

~ from Taiya Selasi’s TED Talk

Don’t Ask Me Where I’m From, Ask Where I’m a Local

When asked where you are from, how do you respond? For some, this question has a straight-forward answer: they are from the place they were born, their national identity being fixed by ancestry, continuity, permanence, perhaps pride. For others, such a question breeds complication and confusion, rather than a sense of security: they were born in one place, with their parents being from others, and grew up somewhere else. ‘Home’ is not necessarily where we were born, but where we feel we belong; it is where we feel safe, where the heart is. In a world characterised by mobility and travel, a refugee crisis and an increasingly troubled discourse on immigration, the concept of a home is increasingly pliable: it can be permanent or transient; comfortable or overwhelmingly alien; a choice or forced upon us. These days, in the digital age, some people only feel at home online, rather than in a physical, tangible place: we occupy emotional homes, as well as our physical ones, and we are incredibly lucky if these concepts align.

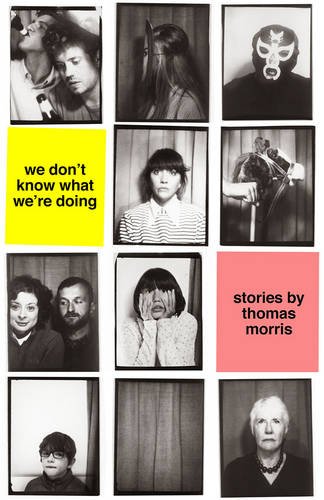

For the characters in Thomas Morris’ collection We Don’t Know What We’re Doing, home is the small Welsh town of Caerphilly. A winding strip of dual carriageway, cutting through the curves of the Rhondda Valley, tethers this place to the locality I have come to call home, Pontypridd. My parents and I moved to Wales from the fast-paced, freeway frenzy of Toronto when I was six, swapping concrete, high-rise towers for lush green pastures and mountaintop views. How rare it is, unless you’re from a major city, to read fiction and identify with the characters’ sense of place so strongly, to know details such as ‘Castell Coch, the roundabout at Nantgarw, the Total Garage on the dual carriageway’, from the story ‘Fugue’. Caerphilly Castle, specifically, a giant gingerbread house falling apart at the iced seams on a bed of verdant fondant grass, is the  axis upon which the collection spins – a focal landmark that links the stories and their inhabitants. The castle, despite being a common, stalwart signifier of setting, is often a symbol of stasis, of torpidity, but these are stories of liminality, of how home can also be a site of a frustration, heightened by familiarity, quiescence and the unknown. In these stories, the microcosm maps onto the macro: Caerphilly becomes a theatre for a play of universal issues, Morris utilising the locale to chronicle the complexities of the human condition, of how place and self are intrinsically linked.

axis upon which the collection spins – a focal landmark that links the stories and their inhabitants. The castle, despite being a common, stalwart signifier of setting, is often a symbol of stasis, of torpidity, but these are stories of liminality, of how home can also be a site of a frustration, heightened by familiarity, quiescence and the unknown. In these stories, the microcosm maps onto the macro: Caerphilly becomes a theatre for a play of universal issues, Morris utilising the locale to chronicle the complexities of the human condition, of how place and self are intrinsically linked.

The paradoxes of home are built into the brickwork of the house at the centre of ‘Castle View’. The protagonist, a primary school teacher employed at the school he himself attended as a boy, is living out a cookie-cutter life. Despite fulfilling society’s expectations, he has failed to find himself and is not emotionally at home in his physical home. The house he and his wife have bought, which is on a sprawling estate of identical boxes, radiates homogeneity and foreshadows his inherent instability: the houses have walls ‘made of plaster’ and his mother has heard stories ‘of people leaning on them and falling through’.

One of the most notable features of Morris’ collection is his ability to shift tone and style to suit character and circumstance, his eagerness to experiment with point of view and narrative technique whilst keeping a firm grasp on symbolism and themes. In ‘Castle View’, a calm, measured, matter-of-fact approach contributes to the pristine facade of happiness that slowly begins to fracture as the story progresses. The tone feels as forced and sterile as the kitchen that ‘always smells of soap powder, and the bathroom air-freshened with Glade’. The protagonist might be able to swipe a crumb of chocolate from the carpet before it dries, even blot the blood from the carpet when he finally cracks and punches the floor incessantly, but he can’t escape from his inherent, internal discord.

The essential irony of the estate is that one can’t actually see the castle: on Google Street View, ‘he’ll move through the street, zooming in on all the other semi-detached houses, all the other small lawns and hedges … but he never sees the castle’. This detail is typical of Morris’ subtle, clever humour that engenders acute observations of the everyday and its hilarious details, but the lack of castle in this story also becomes a melancholic symbol that something crucial is missing from the protagonist’s life – he’s stuck in an emotional labyrinth of identical streets, unable to locate his identity. Sometimes it’s easy to get lost in even the most predictable of places, a reality underscored by the story’s closing scene, an uncanny conflict of the known and the peculiar:

…tonight it seems odd to look out at the garden, and see the contents of the kitchen projected on it all. He knows by memory where everything should be, so it’s strange to see the row of cups where the clothes line should be, the eerie-looking strip-light where the tree should be, and then, finally, to see his image looking back at him from the kitchen window – but it seeming as if he’s still outside, as if he’s standing in the garden looking in.

Morris also explores a very particular, twenty-first-century kind of isolation that is amplified by communication technology, rather than alleviated by it. In ‘Bolt’, the collection’s opening story, the weave of Andy’s relationship with his ex-girlfriend Hannah can’t be fully undone because he still has her phone number. He’s in the home of an attractive, intelligent woman – a psychologist – but when he goes to the bathroom, which ‘like her…smells delightful’, he ‘sit[s] down on the toilet and send[s] Hannah a sad face’.

This simple visual break from the writing serves as a reminder of how words are so very often inadequate. The common emoji is loaded with meaning, applicable to anyone, an expression of shared human emotions. Heartbreak is a knot of  anger, disappointment and regret too tightly tangled to be unpicked with language, and here the image negates the need to. In this moment we empathise with Andy’s impulse, the ease with which he can fold to the temptation to get in touch, and the reality of not really knowing what to say.

anger, disappointment and regret too tightly tangled to be unpicked with language, and here the image negates the need to. In this moment we empathise with Andy’s impulse, the ease with which he can fold to the temptation to get in touch, and the reality of not really knowing what to say.

Morris’ delicate references to modern communication draw attention to how human connections actually fall into varying degrees of disconnect. Later, in bed with the psychologist, Andy ‘[calls] Hannah and [sets] it to speakerphone’, though it is not clear whether she answers. His post-coital dialogue with the psychologist is peppered with his memories of Hannah. When the psychologist asks how he is, he responds vaguely, and secretly admits to the reader that he is actually ‘thinking of Hannah, of our first time in my college room, and how it feels like a very long time ago; how it seems like a line has just been drawn between then and now’. Andy’s ongoing contact (both literally and metaphorically) with his romantic past hinders him from being present and engaging in discourse with the living, breathing human flesh next to him.

Similarly, in ‘Fugue’, a story carefully crafted through second-person narration, the truths about the emotional life of the story’s protagonist are revealed by her interactions with her phone. Bethan is back in Caerphilly for Christmas from a dissatisfying life in Edinburgh:

[It] is like the tiny tag of skin that hangs under your left armpit – you sometimes want to share your fears about it, but you know you can’t face the diagnosis, or rather, you can’t face the embarrassment of having to admit you let it linger for so long.

She seems to have let her relationship linger too long, texting her boyfriend, Tim, to ‘tell him [she] miss[es] him – more out of muscle memory then genuine longing’:

You get changed, dry your hair, do your make-up, then Skype with Tim. He asks him to show him your tits, so you oblige. He tells you all the things he wants to do to you when you’re back in Edinburgh. You tell him that sounds nice.

“I miss you,” he says.

“I miss you too,” you say.

Skype connects Bethan and Tim, but they are just going through the motions: their words are vehicles, devoid of meaning. Connectivity actually fosters something unhealthy, as she needs to be lonely in order to know herself. A productive solitude would be the cure for her loneliness, her inability to be with herself.

While Andy can’t disconnect from his past because of technology, Bethan is having trouble locating hers through it. She’s back in her hometown, but at an emotional remove, and the social media sites that are supposed to preserve memories for society fail to anchor her:

At home, you internet for two hours until your eyes feel dull. You half-read articles on the Guardian, and look at photos of yourself and your old school friends again. When they went away to university, they all came back that first Christmas overweight – the drink, your parents said. And now there are no photos from that year: everyone has de-tagged and deleted them.

Facebook stalking is now a common rhythm in the score of the everyday. It supposedly offers an insight into the lives of others and previous chapters in our own, but this is an ephemeral archive. The contents of an online photo album, as opposed to a tangible one in paper or plastic, can so easily be edited or erased, furthering us from ourselves because we don’t have anything concrete to look back on. Our lived experience is now dominated by the need to preserve it online, but those artefacts fail to help us penetrate what it means to be alive, to be present.

We Don’t Know What We’re Doing is an incredibly insightful, tender collection about the intricate, complex poetry of connections between people, and the places they inhabit. Morris exposes the difficulties we can face even in the most well-known environments, but also leaves room for hope that the struggle will be worth it. At the end of ‘Strange Traffic’, Mrs Morgan returns to Jimmy, having abandoned him on their date, and offers her arm with a smile; as the final story of the collection, the surreal ‘Nos Da’, closes, Lisa ‘takes [Richard’s] hand again, and together they walk to the entrance and Richard steps onto the ice. “Slow,” she whispers. “We’ll take it slow”’. What becomes apparent from these fictions is the real emotional labour and sheer bravery that is required to enact positive change in our lives, to really find home.

~

Sophia Kier-Byfield gained her BA in English Literature from Royal Holloway, University of London, in 2013. After a year of working as a private tutor and travelling the world, she moved to Brighton to pursue a Masters in Modern and Contemporary Literature, Culture and Thought at the university of Sussex, completed with Distinction and department prize in 2015. Soon after, she decided to move to Aarhus to be close to her Danish family and explore this part of her identity. Sophia is currently working as an English Literature teacher at Aarhus University, cycling everywhere and trying to write more. She blogs at sophiakierbyfield.wordpress.com

Sophia Kier-Byfield gained her BA in English Literature from Royal Holloway, University of London, in 2013. After a year of working as a private tutor and travelling the world, she moved to Brighton to pursue a Masters in Modern and Contemporary Literature, Culture and Thought at the university of Sussex, completed with Distinction and department prize in 2015. Soon after, she decided to move to Aarhus to be close to her Danish family and explore this part of her identity. Sophia is currently working as an English Literature teacher at Aarhus University, cycling everywhere and trying to write more. She blogs at sophiakierbyfield.wordpress.com