photo © Matthew Nichols, 2011

In his essay, a runner-up in the 2015 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Richard Buxton rediscovers the American South through the stories of Tim Gautreaux.

Comments from the judging panel:

‘A rich and insightful piece that evokes the power of a story to materialise before us – in the form of people, places, struggles and realisations – as if it were part of our own lived experience’; ‘the author has a storyteller’s gift for detail and language, and their personality shines throughout this essay’.

*

Richard Buxton completed an MA in Creative Writing (dist) at Chichester University in 2014. He has an abiding relationship with America, having studied at Syracuse University in the late eighties. His recently completed novel, Whirligig, is set in Civil War Tennessee, and his short stories typically explore the long shadow cast by that war. One such story, ‘Little Round Top’, was published as the winning entry in the June 2015 issue of Writers’ Forum. He has previously won the Cazart Short Story Prize and placed second in the 2014 Salopian Open Poetry competition. He is a member of the West Sussex Writers and the Historical Novel Association.

Richard Buxton completed an MA in Creative Writing (dist) at Chichester University in 2014. He has an abiding relationship with America, having studied at Syracuse University in the late eighties. His recently completed novel, Whirligig, is set in Civil War Tennessee, and his short stories typically explore the long shadow cast by that war. One such story, ‘Little Round Top’, was published as the winning entry in the June 2015 issue of Writers’ Forum. He has previously won the Cazart Short Story Prize and placed second in the 2014 Salopian Open Poetry competition. He is a member of the West Sussex Writers and the Historical Novel Association.

*

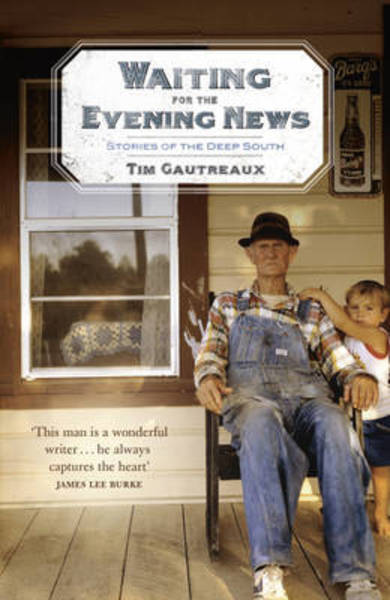

Rediscovering the Deep South: Tim Gautreaux’s Waiting for the Evening News

by Richard Buxton

In February 2001, I found myself in a nameless small town somewhere near Lake Pontchartrain, Louisiana. I was on a ‘tour’ of the Deep South with my soon-to-be best man, Jim. I had an interest in all things Civil War; Jim an interest in all places odd or off-beat. He’d led me into what I assumed to be the local diner. We were badly hungover after two nights in New Orleans. I was eating grits as an experiment and something akin to deep fried Spam. The food was a poor substitute for a full-English, but it did its stodgy best for me. The tables were covered in loose waxed paper. We drank iced-water from tall, red plastic tumblers. I looked at the clientele: men sported moustaches thick enough to polish shoes with; women stretched even more low-slung elastic than their husbands. Maybe we’d mistakenly come into an old people’s home or a day care centre. I recall it as somewhere I didn’t understand and for which I had no terms of reference. Just another of Jim’s off-beat stops – a small place on the way to a big place. All I knew was that this was Cajun country, drained swampland dotted with any number of small towns all looking much the same. We’d driven through several getting here, in our Grand Cherokee. Riding shotgun, once or twice I’d indulged in a long yawn and missed a whole town.

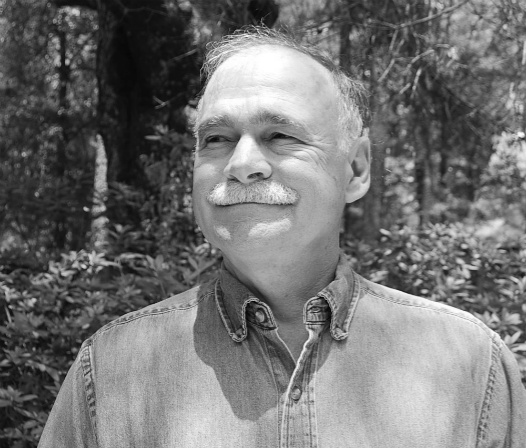

It’s from such places that Tim Gautreaux might find characters for one of his almost two dozen stories in Waiting for the Evening News. He lives in Hammond, just up the road, and knows all about Louisiana and all about its Cajun people. He’s one of them, as his surname implies. The book is full of Gallic names: Boudreaux, Thibodeaux, LeBlanc, Placervent. This book, published in 2010, is the sum of his two earlier collections, Same Place, Same Things and Welding with Children.

Thirteen years later, Jim gave me Waiting for the Evening News as a birthday present, around the time I was finishing the taught element of a creative writing M.A. There had been months of prescribed reading, and I’d been experimenting with my own short stories, usually feeling as if I was trying to straight-jacket a tale into two thousand words. By comparison, Tim Gautreaux’s stories felt like a slow walk by the sea. I instantly fell in love with the spaciousness of the prose. His stories are in the five to six thousand word range – long enough to get to know a protagonist, spend some time on the place and still have the freedom for a few secondary characters.

Thirteen years later, Jim gave me Waiting for the Evening News as a birthday present, around the time I was finishing the taught element of a creative writing M.A. There had been months of prescribed reading, and I’d been experimenting with my own short stories, usually feeling as if I was trying to straight-jacket a tale into two thousand words. By comparison, Tim Gautreaux’s stories felt like a slow walk by the sea. I instantly fell in love with the spaciousness of the prose. His stories are in the five to six thousand word range – long enough to get to know a protagonist, spend some time on the place and still have the freedom for a few secondary characters.

As I moved from one Gautreaux story to another – from a drunk train driver on the run, to a tall-story competition on a Mississippi cargo boat, to a priest blackmailed into returning a stolen car for a parishioner – I became aware of a creeping jealousy of Tim Gautreaux’s provenance. These stories are replete with his love and understanding of his home – he’s the son of a tugboat captain and grandson of a steamboat engineer. He once said, in an interview with Maria Hebert-Leiter, that it was only when he left Louisiana to attend the University of South Carolina that he realised ‘how different Louisiana was, south Louisiana in particular, from the rest of the country […] the food […] the religion […] the politics.’ That might seem strange to British readers – although we’re used to a different accent every fifty miles, we don’t always expect America to be parochial. Waiting For The Evening News reminds us that, while America may be a great melting pot for the world’s peoples, some of its ingredients withstood the heat longer than others. Cajun culture is such a case: the tough meat in the spiced stew. It’s rarely portrayed from an insider’s viewpoint.

This reminded me of another American flavour that sits outside our expectations: Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon Days, his fictional small town in Minnesota full of imported Nordic Lutherans and Catholics, constantly at odds. It’s somehow reassuring to find these American anomalies. Interestingly, similar to the friction between Keillor’s Lutherans and Catholics, Gautreaux has an enemy for his Cajuns to square up to. The more obvious target might have been Yankees from the North, tourists or businessmen on the make, but he steers clear of this broader Southern narrative. Instead, he uses Texas as a more local nemesis. It’s only the other side of the swamp after all, where, for Gautreaux, the land is unnaturally dry and the people are full of themselves and their oily ways. Gautreaux tells his stories from well back on the Cajun side of the fence. More than once a Texan is bettered. In ‘Floyd’s Girl’, a violent stepfather tries to steal a child across the state border. After he is bested, he’s flown off in a bi-plane and gloriously dumped by parachute back into the Lone Star State. As if the plane wouldn’t want to dirty itself by landing there.

It would be wrong to suggest Gautreaux uses exclusively Cajun lead characters. More precisely he writes from a white, blue-collar perspective that mirrors his own childhood experience. It’s just that in his bend of the bayou the majority of white, blue-collar workers are Cajun. It’s sometimes unclear which decade you’ve pitched up in. Some stories are set as far back as the Great Depression; others are almost present day. He clearly has a great deal of affection for the times closest to his childhood. Quoted by Margaret Donovan Bauer, in Understanding Tim Gautreaux, he says:

You know, there’s one thing about the old days, the fifties, when everybody believed in two or three things […] not unlimited roll your own philosophy – which is what we have today.

He’s careful not to let sentiment show overtly in the stories. ‘Avoiding sentimentality is easy to do,’ he said, in an interview from Conversations with Tim Gautreaux, edited by L. Lamar Nisly. ‘Use not one cliché. Use as little exposition as possible. Focus on action and detail that in a subtle way suggests what you want to say.’

The book is full of machines of all sorts, and Gautreaux provides abundant believable detail on their operation. Stories include a half-mile long diesel train, a speeding juggernaut, and a tugboat crewed by out-of-work writers. It’s the same with smaller machines too: we learn the essentials of a field pump and the inner workings of a piano. ‘Contraptions’ my father would have called them. His characters’ competence or incompetence, and their rectitude, is measured by their mastery of these machines. We can trust the piano tuner in all things because he’s diligent, a perfectionist. Less so the diesel engine driver, who takes his machine for granted and drinks on the job. And our writerly tugboat crew? I’m afraid their minds are on the wrong job altogether.

Gautreaux’s exploration of what he perceives as a less morally complex past seems to be reflected in his beloved contraptions. They are made of honest, hard-working oiled cogs and gears. We have a chance of understanding them in the same way as we understand his straightforward characters. His protagonists are armed with a simple list of dos and don’ts. If you break something, then set it right and don’t feel good about it until you do. It’s the extraordinary situations his characters find themselves in that shine a light on their moral code.

Almost all the stories are in close, third-person perspectives. From a stylistic angle, they are not remotely experimental. But the languid feel disguises an underlying efficiency. Early in ‘The Piano Tuner’, Claude hasn’t been to tune Michelle’s piano for a whole year.

He stopped under a crepe myrtle growing by the porch, noticing that the yard hadn’t been cut in a month and the spears of grass were turning to seed. The porch was sagging into a long frown, and the twelve steps that led to it bounced like a trampoline as he went up.

We see the place clearly through the evocative description, but we are also being introduced to the protagonists. Claude has a precise eye and disapproves of the neglect. Before we meet Michelle, through Claude, we see her as letting the place, and possibly herself, get run down.  Characters are often carefully chosen to give them a privileged, insider perspective on the lives of strangers. As well as the piano tuner, there’s a house fumigator, a pump repair man, a priest. They all encounter the hidden desperation of others.

Characters are often carefully chosen to give them a privileged, insider perspective on the lives of strangers. As well as the piano tuner, there’s a house fumigator, a pump repair man, a priest. They all encounter the hidden desperation of others.

Only once in the whole collection does a story stray into New Orleans, as if it’s lost its way. New Orleans is almost as evil as Texas and, for the most part, we stay in small towns or on remote, flat, farms. There’s the permanent impression that there’s a great deal of sky above you, and that nothing of great moment has happened here for a very long time. The frontier swept west almost two centuries ago, but barely stopped in Louisiana for the weekend. This has always been a backwater; most of the landscape is composed of backwater. Gautreaux exposes the quiet despair, the love and the humour of his people. In ‘Welding with Children’, Bruton is distressed at how his grandchildren are being brought up. Eventually he gives up on affecting any change through his children, and builds the little ones a tyre swing. Often Gautreaux is telling us: ‘It’s that simple. Do what you can.’

Many of the protagonists are old-timers, porch dwellers, struggling to make sense of a changing world. Rather than let them rock away their last years, Gautreaux sets them new challenges. In ‘The Courtship of Merlin LeBlanc’, Merlin finds he needs to care for his baby granddaughter after his daughter dies in a plane accident. His father, and then – quite wonderfully – his grandfather turn up to deliver advice and common sense as if Merlin were still a boy. Gautreaux has five generations in play and creates a wonderful perspective on love and care. In ‘Easy Pickings’, a car thief from evil Texas crosses the border and thinks he can bully and rob an old Cajun woman. She feeds him home cooking until help can arrive. It has the feel of a Br’er Rabbit tale – the car thief is Br’er Fox – but wisdom wins out when he’s seduced by the chicken stew. ‘She lifted a lid, and a nimbus laden with smells of onion, garlic, bell pepper nut-brown rous rose like a spirit out of the cast iron pot.’

Many stories depict society’s fading veneration for the old. Yet Gautreaux doesn’t portray them as victims: they are understated heroes and heroines who can look out for themselves. Age is an asset. I shouldn’t leave the impression that all the main characters are in their twilight years, but a preponderance of them might be patrons of my Lake Pontchartrain OAP diner. If I returned there today, as I tackled my Jell-O and whipped cream dessert with a plastic spoon, I think I’d see the clientele quite differently. Gautreaux has, through the medium of the short story, lovingly introduced me to Louisiana and its people more completely than a single novel ever could. I’d imagine myself surrounded by a caring piano tuner, a struggling single grandparent, riverboat engineers, a childless house fumigator, a woman farmer-come-helicopter co-pilot. Their children might be speeding truck drivers needing to slow their lives down, young men laid-off who drive into Texas only to see more clearly their home is in Louisiana. I think I’d feel a borrowed affection for the people around me, an awareness of their struggles, their honesty and measured hope. In other words, through the people, I’d feel a sense of place.