(Image © Jakubowski Foto) *

NO MEAN FEAT

by TRACY FELLS

~

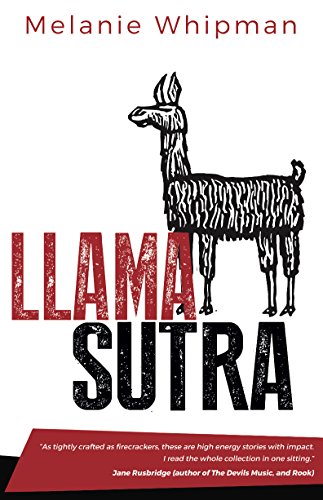

On the cover of Melanie Whipman’s debut collection Llama Sutra, author Jane Rusbridge declares: ‘these are high-energy stories with impact. I read the whole collection in one sitting.’ The collection had a similar effect on me; one story was never enough and I had to keep reading. All my favourite themes are in here: fairytales and folklore nestling between gritty, contemporary tales of love and passion, the uncanny and the quirky woven through with dark and sinister threads.

Funny, surprising and at times shocking, many of these stories come with a pedigree; the acknowledgements page reads like a roll call of competition awards: The New Writer, the Bristol Short Story Prize, the Rubery Book Award, the InkTears Prize, the Prolitzer Prize. I’m both a reader and a writer of short stories. I also enter a lot of writing competitions and once shared a shortlist with Melanie Whipman, in the 2014 Write Idea Prize. Whipman won – with ‘What You’d Do for Love’, included in Llama Sutra – and to this day continues to excel in short story competitions. To me, this collection should be read only for pleasure, but also for instruction. If you’re a fiction writer hoping to hook the interest of a competition judge then you should study this collection with an analytical eye, learn what makes a winning short story.

The first line of a story is critical to drawing in a reader, editor or judge, but for me it’s often the title – the more offbeat or quirky ones tempting me to start reading. With the lead story titled ‘Llama Sutra’, how could anyone resist wanting to read on? The opening paragraph continues the enticement: ‘The llama winks at me. The liquorice lashes of its left eye sweep down for a long second, then up again.’ Like many of Whipman’s stories, this begins in medias res, literally kicking off in the middle of the narrative. There are no laborious introductions to the characters, we’re living their lives right from the start, and what initially seems to be a story about llamas quickly becomes so much more. The narrator and her husband, Simon, are desperate for a baby, but she’s struggling to get pregnant due to his low sperm count. They start IVF:

Weeks of hormone injections and petroleum-gloved internals and sniffing syneral for me. Simon agrees to do my injections at home. He practices on an orange. The nurse draws a smiley face on it in black felt-tip, and then the same circle and grinning mouth high on my right buttock.

However, the process is without success. Failure is straining their relationship and Simon doesn’t want to adopt or use a sperm donor, as ‘he doesn’t like the thought of something ‘alien’ in our home’.

However, the process is without success. Failure is straining their relationship and Simon doesn’t want to adopt or use a sperm donor, as ‘he doesn’t like the thought of something ‘alien’ in our home’.

The first person narrator is never named, but the immediacy of using present tense immerses us in her world, and we’re swept along, eager to learn the outcome of the couple’s IVF journey. When their third attempt doesn’t take, she finds herself ‘looking at men who look like Simon’. She then begins helping at a local llama farm, where she sees the animals mating. Her fascination and longing is clear: llamas seem to have mastered the art of loving and copulation. The story concludes after a successful, and unusually long, pregnancy where a brief flash of magical realism spits you in the eye. Not only did this story win the InkTears Short Story Contest, but it was also chosen for broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

‘After the Flood’ tells what happened after the great Biblical flood: ‘I can’t sit still these days. Noah shakes his head and says an arse the size of mine is designed for sitting on. But I can’t settle.’ Mrs Noah wistfully shares how she’s coping (or not) with life back on land without the sea.

If I close my eyes I can still hear it. The creaking of the timber, the slap of the water, the grunts and squeaks and whinnies and squawks. It’s the silence here I find – difficult. The stillness. I have a shell in every room now […] When I walk through the house I hold them to my ear, listen to the sea trapped inside.

Breathing new life into an ancient tale, twisting the familiar, can be a favourite theme for competition judges. In this story, Whipman creates a setting that feels contemporary, as a journalist seeks an interview with Mrs Noah. The language she uses for Mrs Noah’s narration juxtaposes the lyrical heart murmurs of a poet with the no-nonsense grumblings of a long-suffering wife, bringing her to life. We believe her story, no matter how fantastic it gets, because we accept Mrs Noah as one of us. There’s humour here, but menace too: Noah is ‘brooding, swollen with malice and wine’; it no longer feels a happy marriage. We learn she betrayed Noah on the ark, with one of his beasts. I loved how this at first comic story turns bittersweet as Mrs Noah discovers her husband has set off to hunt a lion that’s been ‘sniffing round. Stalking the women, one by one’. It’s not hard to guess this is Mrs Noah’s lion.

That honeyed hide beneath my thighs and the dandelion down of his stomach. Nothing was ever so soft. You could blow it away with one whispered kiss. And the bat of his paw. Like the brush of butterfly’s wings.

We feel her sadness and grieve for all that she lost after the flood.

It seems that in a competition or literary journal’s slush-pile, fantastical stories often stand out and do well. I believe Whipman’s true skill comes in wryly perverting recognisable folktales. In ‘After Ever After’, Rapunzel is now married to her prince. Rapunzel let down her hair and killed the wicked witch, yet she’s still stuck in the tower, yearning to be free of her prince’s cloying fears. The happy royal marriage ending is just another form of prison for Rapunzel.

Now I see no one but the staff. He fears for my life. Dogs and soldiers patrol the garden. […] He comes home with stories of witches disguised as travelling saleswomen. Hair combs spiked with poison, apples that kill, belts that tighten and suffocate.

Rapunzel tells her story in the present tense, her words tumbling fast and furious as if time is running out, making us believe this could be happening right now. The slick pace of storytelling continues, unlike a typical languid fairytale, and we stick close to Rapunzel right to the end – urging her on to ‘take a breath and let go’.

I love magical realism and often weave it into my own short stories, though it’s not to everyone’s tastes. Whipman appears to be of the same opinion, as the stories in the collection effortlessly switch to realism with contemporary themes, demonstrated by the Prolitzer Prize winning story ‘Dissolving’ – a blunt and shocking account of two kidnapped men sharing a cell. By leaving the narrator unnamed, Whipman allows us to view him as anyone’s son or husband. The kidnapping is of workers in an office, and this made me think of how terrorism can strike so randomly, in an environment we recognise as normal. This is the true horror simmering beneath Whipman’s blokey prose: the fear that it could happen to any of us. A simple sugar cube is the catalyst unleashing memories and leading to a personal act of rebellion as the men prepare for execution.

I love magical realism and often weave it into my own short stories, though it’s not to everyone’s tastes. Whipman appears to be of the same opinion, as the stories in the collection effortlessly switch to realism with contemporary themes, demonstrated by the Prolitzer Prize winning story ‘Dissolving’ – a blunt and shocking account of two kidnapped men sharing a cell. By leaving the narrator unnamed, Whipman allows us to view him as anyone’s son or husband. The kidnapping is of workers in an office, and this made me think of how terrorism can strike so randomly, in an environment we recognise as normal. This is the true horror simmering beneath Whipman’s blokey prose: the fear that it could happen to any of us. A simple sugar cube is the catalyst unleashing memories and leading to a personal act of rebellion as the men prepare for execution.

A compelling character voice in a short story sucks in a reader and keeps them reading to the end. I envy Whipman’s talent for creating teenage characters. Her sharp, no-nonsense dialogue, often paired with lyrical prose, is a key element of her writing. The pain, bewilderment and sheer agony of youth are displayed in stories such as ‘What You’d Do for Love’, ‘Suicide Bomber’, ‘Clipping Kiki’ and the heart-pounding ‘Silent as Storks’, which was shortlisted for the Royal Academy Pin Drop Award and the Fish Short Story Prize. In ‘Silent as Storks’, Whipman’s teenage voice is at its best as fifteen-year-old Fin is supposed to take his little sister, Grace, to visit their mum in hospital. Instead, Fin prepares to offer up Grace to a glue-sniffing gang in exchange for the return of his dad’s watch, pinched off him:

It’s not like they’re going to hurt her, Darren’s a vicious git, but he’s got limits. All he wants is a look, the sick wanker […] There’s no reason I should feel so odd, but I’ve got the same acidic wave pushing at the back of my throat as when I did cross-country. My stomach feels like the day Dad left […] Afterwards I spewed up alphabet spaghetti, and tried to make some sort of sense out of the mangled letters on my trainers.

Her teenagers are mouthy, at times foul in thoughts and deed, but they’re still vulnerable kids longing for a happy ending.

As a fiction writer, I’ve tried to pick apart these stories, to learn Whipman’s tricks and use them in my own writing. But then I reach a story that makes me want to give up, because I wonder if I’ll ever write anything as good. ‘Matador’ is stuffed with sensuous and sumptuous language, and is about food and sex. In a domestic setting, a battle plays out between the narrator and her lover, replicating the arrogance and control of a matador’s bullring performance. A threat simmers under the narrative, where Den’s obsessional demands for fresh home-made pasta makes me worried, scared for the narrator, when all she can offer is defrosted linguine.

“Linguine okay?” You hold up the tub of brittle ribbons, your voice as light as air, a gone-already feeling in your groin.

“Don’t worry. No hurry. Make some fresh. I can wait.” His voice is as light as zabaglione.

Using second-person narration, for me, only adds to the tautness and tension that stretches throughout the story, like elastic spaghetti, and you know one day it’s going to snap. In a big way.

If you’re hoping for a quick fix, planning on just dipping in to read one story at a time, then pick up Llama Sutra at your peril. You’ll find this intriguing mixture, a hybrid of folklore and contemporary storytelling, hard to resist. As a reader I was mesmerised by the twists and shocks woven into the stories, feeling much like poor Simon in ‘Llama Sutra’ when he catches sight of ‘the little cloven hoof’ belonging to the new baby his wife is cradling. As a writer, I’m still trying to fathom how Melanie Whipman did it, how she created such a variety of genre-crossing, award-winning and readable stories. Don’t spend your money on ‘how to’ writing guides, instead get your own copy of Llama Sutra, read it first for pleasure, then read it again to learn how a true storyteller satisfies all the demands of readers, editors and judges. That’s no mean feat.

~

Tracy Fells has won awards for both fiction and drama. Her short stories have appeared in Firewords Quarterly and Popshot magazine, online at Litro New York, Short Story Sunday and in anthologies such as Willesden Herald New Short Stories (9), Rattle Tale, Fugue and A Box of Stars Beneath the Bed. Competition success includes short-listings for the Commonwealth Writers, Willesden Herald, Brighton and Fish Short Story prizes. Tracy completed her MA in Creative Writing at Chichester University in 2016 and is currently seeking representation for a crime novel and her short story collection. She shares a blog with The Literary Pig and tweets as @theliterarypig.

Tracy Fells has won awards for both fiction and drama. Her short stories have appeared in Firewords Quarterly and Popshot magazine, online at Litro New York, Short Story Sunday and in anthologies such as Willesden Herald New Short Stories (9), Rattle Tale, Fugue and A Box of Stars Beneath the Bed. Competition success includes short-listings for the Commonwealth Writers, Willesden Herald, Brighton and Fish Short Story prizes. Tracy completed her MA in Creative Writing at Chichester University in 2016 and is currently seeking representation for a crime novel and her short story collection. She shares a blog with The Literary Pig and tweets as @theliterarypig.

One thought on “No Mean Feat”

Comments are closed.