photo by Infil Trator

by Carol Fenlon

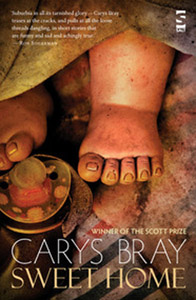

Carys Bray’s debut short story collection, Sweet Home, seems at first to be aptly named. These are stories of family life, at times utterly domestic. Yet the reader soon finds that the homes described are far from sweet.

Human failings and the random nature of life’s tragedies intertwine to present the precarious realities of family and individual lives, as each story hurls a different disaster at the reader. With a mixture of black humour and delicate sympathy, Bray explores social exclusion,  childlessness, mental illness, old age, drug addiction, divorce, and life-changing illness and death. The prose is poignant and draws the reader in to the frailties of her characters.

childlessness, mental illness, old age, drug addiction, divorce, and life-changing illness and death. The prose is poignant and draws the reader in to the frailties of her characters.

Her emphasis on the human condition raises these stories above the merely domestic, or issues specific to men or women, and into the universal. Our identities and coping mechanisms are forged by family life and so, I would imagine, all of us have been touched by at least one of the situations she examines.

In this collection, guilt – specifically parental guilt – is a major factor in the shaping of personality. While women’s guilt is perhaps a well worn theme, Bray extends the perspective to all parents. The obsessive-compulsive father in ‘The Countdown’ blames himself for a multitude of imagined disasters even before his child is born:

He leans over the deep farmhouse sink to retrieve something from the windowsill… Then he drops her… She splinters into slivers of bone and connective tissue… His wife is coming and he can’t jigsaw the fragments in the sink into anything that resembles a baby.

His fears and actions have their roots in his own childhood, a cycle to which Bray returns frequently.

Parents in these stories measure themselves against an internalised ideal, which they can never hope to achieve. Sometimes the characters recognise this, accepting that there are moments when they succeed and hoping that these small successes will make up for their failures. Sometimes, even limited success is beyond the character’s reach; the father in ‘The Rescue’ plods blindly on, trying fruitlessly to help his drug addicted son. Here, the domestic tragedy is played out against the backdrop of the rescue of the Chilean miners in 2010. Sadly, there is no heroic rescue team to come to his aid.

Equipped with a Say-No-To-Drugs book and audiocassette, he set out to winch the son to safety.

“Just say no,” he pleaded.

The son laughed. “Oh, fuck off, Dad,” he said.

In Bray’s fiction, social support systems and expert advice fail to deal with the practical realities of family dysfunction. Textbook analyses bear little relation to real life. Her characters internalise advice from medical experts, books and TV. They suffer peer pressure from other parents who regurgitate the same ideas and, in stories such as ‘Everything a Parent Needs to Know’, they are undermined by their own parents, who attempt to impress their thoughts on how children should be raised.

In both ‘Everything a Parent Needs to Know’ and ‘I Will Never Disappoint My Children’, Bray shows incisively how the image of the ideal parent we hope to be is often formed by our parents’ failings and our remembered pain from those times. But the characters in these stories are doomed to fail as history repeats itself. The mother in ‘I Will Never Disappoint My Children’ deprives her daughter of a promised ice cream, just as her father had once deprived her.

The stories in this collection are permeated by loss. Sometimes this loss comes in the form of an unexpected tragedy, such as the death of a child in ‘Scaling Never’ or ‘Bed Rest’. In other stories, Bray explores the loss of mental faculty from old age, or the loss of identity caused by invasive surgery in ‘Under Covers’. But there is nothing maudlin in this  writing. Bray avoids sentimentality with black humour and scalpel-sharp detail to reveal the mechanisms by which humans deal with the horrors life can throw at them.

writing. Bray avoids sentimentality with black humour and scalpel-sharp detail to reveal the mechanisms by which humans deal with the horrors life can throw at them.

When the worst happens, everything fails. Advice and learning go out of the window and the ground dissolves beneath our feet. After Issy’s death in ‘Scaling Never’, her brother digs up a dead bird they had buried, trying to make sense of the death. Miracles, magic and the religious beliefs of his family combine in the confused thoughts of the child as he desperately attempts to resurrect the bird and then, hopefully, his sister.

Jacob felt cross [with his father]. “So it’s all right then in the end for Issy to be dead?” he asked.

“Didn’t you even try to make a miracle happen? What’s the point of being in charge at church if you can’t do miracles?”

Throughout the collection, character’s use fantasy as a coping mechanism. In ‘Bodies’, the children replay death rituals, holding mock funerals; their way of coming to terms with death, making it smaller and less frightening. In ‘The Ice Baby’, Bray mixes fantasy and fairytale to bring the illusion of a much-wanted child to a barren couple. In a more realistic tale, ‘Under Covers’, Carol exchanges the realities of her mundane marriage for a fantasy of exotic encounters, fuelled by romance novels. The young girls who laugh at her, in fact, are following in her footsteps with their romantic ideals of expert lovers, drawn from films and television shows. Ultimately,however, it is the real love of Carol’s husband that eclipses her romantic fantasies.

She was a little surprised when he slipped a finger into the side of her dress, and under the edge of her bra. She stood very still as he explored the knotted edge of scar tissue.

“There you are,” he said, “love is not love which alters when it alteration finds.”

Despite Bray’s focus on loss, guilt, and random tragedy, it is love that ties the family together, that makes things seem possible, that softens the inevitable, and just occasionally effects a miracle. It is the father’s love in ‘The Rescue’ that keeps him doggedly trying to help his son and prevents him from giving up. Bray shows us that love triumphs where other ideals fail.

~

Sweet Home won the Scott Prize in 2012 and Bray’s debut novel, A Song for Issy Bradley, is due to be published by Hutchinson in June.