('Haunted' © Houman-thebrave, 2014)

*

“EVERY EVIL ROOTED IN ITS STONE”:

THE GOTHIC IMAGINATION IN ‘THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER’

by CHRIS MACHELL

*

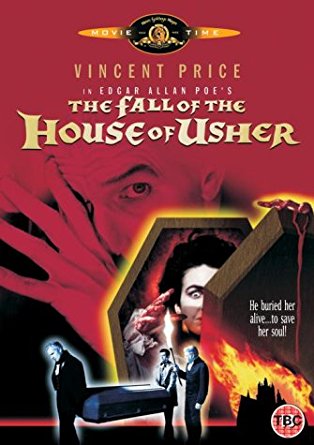

Filmmakers have adapted, parodied and paid homage to Edgar Allan Poe’s works countless times, none more so than the notoriously prolific master of schlock, Roger Corman. Corman adapted no fewer than eight of Poe’s stories into films, the 1960 adaptation of The Fall of the House of Usher being the first of his Poe Cycle. The story itself has been adapted into film numerous times: 1928 saw two versions of the story, an American short taking its cue from German expressionist masterpiece The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and a French feature from Jean Epstein. There is also a 1950 British version of the story, a modernised version from 2006, and a surprisingly good 2012 animated short film, aptly narrated by Christopher Lee. There are several other versions, but Corman’s version has endured the most.

House of Usher is perhaps Corman’s most interesting adaptation in that, departing quite drastically from Poe’s narrative, it still captures the excess of Poe’s gothic aesthetic. Retaining the histrionics of Poe’s story, Corman’s House of Usher represents Poe’s imaginative hyper-reality with vivid, saturated colour, a wildly over the top central performance from Vincent Price, and a pulpy, kitsch sensibility.

Poe’s story is narrated by an unnamed hero who receives a letter from his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher. Usher pleads with the narrator to visit him ‘as his best, and indeed his only personal friend, with a view of attempting, by the cheerfulness of my society, some alleviation of his malady’. The sight that greets the narrator on his arrival at Usher’s residence is one of singular gloom, in which ‘minute fungi’ have overgrown the exterior of the house, the surrounding trees are ‘white and decayed’, and the tarn that sits in front of the house is ‘black and lurid’.

Poe’s story is narrated by an unnamed hero who receives a letter from his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher. Usher pleads with the narrator to visit him ‘as his best, and indeed his only personal friend, with a view of attempting, by the cheerfulness of my society, some alleviation of his malady’. The sight that greets the narrator on his arrival at Usher’s residence is one of singular gloom, in which ‘minute fungi’ have overgrown the exterior of the house, the surrounding trees are ‘white and decayed’, and the tarn that sits in front of the house is ‘black and lurid’.

Never one for descriptive subtlety, Poe leaves us in no doubt that the oppressive mood is not so much a result of the aesthetic features of the house, but more its psychological effect on the viewer. A mirror of Roderick Usher’s mental state, the windows ‘are eye-like and vacant’, and the abyss-like tarn has a precipitous brink, as if it could swallow up sanity itself. Indeed, with a ‘sullen’ mood and ‘rank miasmas’, which apparently induce ‘bewildering’ apparitions, the tarn is imbued with its own mad psychology.

The narrator looks upon the sorry scene:

…with an utter depression of soul, which I can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the afterdream of the reveller upon opium […] There was an icinesss, a sinking, a sickening of the heart – an unredeemed dreariness of thought which no goading of the imagination could torture into aught of the sublime.

The reference to opium and dreams highlight the narrator’s imaginative vision of the scene, blurring the lines between subjective interpretation and objective description. The narrator then notes ‘the perfect keeping of the character of the premises with the accredited character of the people […] speculating upon the possible influence which the one, in the long lapse of centuries, might have exercised upon the other’, implying a metaphysical merging of the two. Moreover, the Usher family tree is a straight line of father to son. With no ‘collateral issue’, the narrator suggests, the line has turned in on itself, and the House of Usher, as both family and building are collapsing into sickness and decay.

The house is less a reflection of Usher’s psychology than its literal manifestation, where the physical and metaphysical have become indistinguishable. Psychic buildings are a hallmark not just of Poe’s work, but of popular Gothic fiction overall, from the labyrinthine fortress in The Castle of Otranto, to the hotel of The Shining, and the eponymous house in Guillermo del Toro’s 2015 film Crimson Peak, a self-described ‘gothic romance’ heavily inspired by both Poe’s original tale and Corman’s adaptation.

Corman’s House of Usher is a vision of excess: perpetual thunderstorms batter the heavy velvet curtains of high windows. The occupants of the house, described as melancholic wastrels in Poe’s text, are animated into sickly life on the screen, clad in gaudy crimson and garish blue, all rolling eyes and melodramatic gestures. As in Poe’s story, Usher is hypersensitive to ‘the faintest’ light and noise, a fitting malady for a character conjured to life by the sound and light of the cinema screen.

The narrator, named in the film as Philip Winthrop and played by a deliciously wooden Mark Damon, has come to visit Usher’s sister, Madeline, whom he met in Boston. In Poe’s story, Madeline is a stranger to the narrator before she dies, returning from the grave to frighten Roderick to death and bring about the destruction of the House.

Madeline’s role in Corman’s film, meanwhile, is significantly expanded. Engaged to Philip, she is confined to the house by her brother, who is re-imagined as a sort of hypochondriac tyrant. Roderick, played by the inimitably over the top Vincent Price, believes that the Usher line carries an inherited evil which can only be stopped by preventing his sister from marrying and having children. Ultimately, Usher achieves his goal by knowingly entombing his sister alive (twice!) before she returns to wreak her revenge, dovetailing with Poe’s original ending.

Madeline’s role in Corman’s film, meanwhile, is significantly expanded. Engaged to Philip, she is confined to the house by her brother, who is re-imagined as a sort of hypochondriac tyrant. Roderick, played by the inimitably over the top Vincent Price, believes that the Usher line carries an inherited evil which can only be stopped by preventing his sister from marrying and having children. Ultimately, Usher achieves his goal by knowingly entombing his sister alive (twice!) before she returns to wreak her revenge, dovetailing with Poe’s original ending.

The Mad Trist – the poem that the narrator reads to Usher at the story’s climax – is excised from the film, but in its place is a wonderfully overcooked scene involving Usher’s ancestral portraits. The paintings’ modern style, clearly mimicking the work of Francis Bacon, is undoubtedly anachronistic yet their baroque sensationalism is in keeping with Corman’s own lurid aesthetic, and retains Poe’s self-conscious gothicism. The paintings and The Mad Trist both signify the breakdown between representation and reality, Price’s Usher believing that his ancestors’ crimes are an evil manifesting in both his bloodline and his home.

In one sense, The Fall of the House of Usher is about our tendency to imbue human psychological qualities on to inanimate objects. As Philip puts it: ‘the house, sir, is neither normal nor abnormal. It is only a house.’ Nevertheless, Philip succumbs to his host’s suggestions with a surreal nightmare where Usher’s ancestors beckon him to join them, whereas in Poe’s text the narrator describes the tarn and the house in psychological terms.

The house’s collapse into the tarn represents psychological order succumbing to formless imaginative chaos, underscored by the sounds of The Mad Trist breaking through into reality at the short story’s climax. In the film, the house’s collapse can be read as the weight of Usher’s sins against his sister collapsing in on itself. Usher’s obsession with the house drives him to entomb Madeline, and in so doing, creates a self-fulfilling prophecy of his own evil as embodied by the house. In both versions, however, it is not whether the house is ‘really’ evil that matters, nor whether its collapse is literally connected to Usher’s malady. Rather, the importance is in the associations that the reader and viewer draws between the characters and their environment. Imposing human psychology on to the physical world is a natural function of imaginative fiction. But in the gothic imagination of The Fall of the House of Usher, it is the first step in dismantling the wall of sanity that separates the literal from the figurative.

~

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack.

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack.

His favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is the cult Sega classic, Shenmue.

2 thoughts on “Gothic Imagination in ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’”

Comments are closed.