('Traveller' © Jens Schott Knudsen, 2013)

FICTIONAL WORLDS

by JANIS LANE

This story starts years ago, with my discovery of Rose Tremain’s work during the early weeks of a Masters degree in Creative Writing. Course notes included comment by Robert Graham taken from his creative writing companion The Road to Somewhere, in which he asserts:

Tremain is one of the finest British contemporary novelists […] much can be learned by studying her work. Hers is always a beautifully realised fictional world, finely textured without ever being dense.

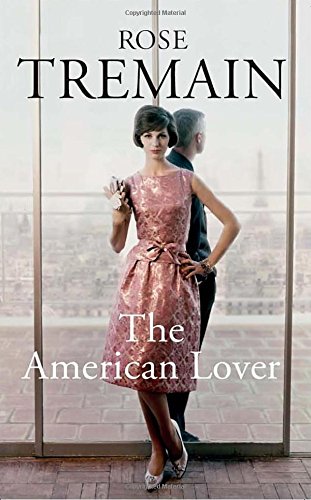

This is also true of Tremain’s handling of the short form. Her most recent collection, The Amercian Lover, is full of these worlds – a standout collection with beautifully realised characters and compelling narratives told at a measured pace. The Oxford English Dictionary definitions for the word ‘tragedy’ summarise the themes of this collection well:

1. An event causing great suffering, destruction, and distress, such as a serious accident, crime, or natural catastrophe

2. A play dealing with tragic events and having an unhappy ending, especially one concerning the downfall of the main character

Tremain handles the tragedies that befall the protagonists of The American Lover with such lightness of touch that a reader will view their downfall with the fondness of a concerned relative; they are so well drawn as to be universally sympathetic. These tragedies are threaded throughout, ranging from high drama and death, to minor inconveniences, such as the departure of a spouse or lost love. The uniting factor is the characters’ vulnerability, and, often, a lack of control over their own destinies. Tremain is not afraid to show her hand early in these stories: our sympathies are positioned from the outset but the narrative is never compromised.

The title story (shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award in 2014) tells us of Beth’s lost love as she recounts the story of her life to her housekeeper, Rosalita. The manner in which Beth describes sexual antics with her American lover is laced with the vulnerability of one who has been taken advantage of: “I can remember that feeling of floating out of my life, while fellatio was taking place.” This is further reinforced by Rosalita’s reaction, as she whispers, “Such things you have seen. Try to forget them now.”

Beth becomes a shadow of herself, feeling trapped in her apartment after shattering her leg in a car crash. She is nearly thirty and entirely accepting of her lot. ‘She had no life … She was being forgotten.’ These ideas are cemented by the final and complete rejection by her American lover: a brief glimpse in Harrods, he sees her and walks on. Beth is powerless, trapped by her physical limitations even when not physically trapped in her apartment. She wants to follow him, ‘her heart cries out’ for it, but ‘her body is too slow. Her legs won’t let her run’ – leaving the reader’s heart as stricken as Beth’s surely is.

In ‘Captive’ we see a different sense of being trapped. Owen is ‘fifty and alone’. Forced to sell the family farm when his parents die, he opens a boarding kennels on a smaller piece of land. Owen is a fair man and includes all breeds of dog, no matter how dangerous, as he ‘felt some affection for all animals.’ As in so many of her stories, Tremain’s light touch paints a three-dimensional world and vivid character: Owen’s very human nature is what  brings about his downfall. When the cold snap arrives in this brief story, we see his optimism and purpose replaced by grim realisation: ‘He and the animals are imprisoned for all time in a frozen world.’

brings about his downfall. When the cold snap arrives in this brief story, we see his optimism and purpose replaced by grim realisation: ‘He and the animals are imprisoned for all time in a frozen world.’

At the end of the story the title resonates further, as Owen takes refuge in his bungalow and the noise of the baying dogs comes to him ‘from a barbaric place … the sort of place he’d hoped never to inhabit.’ The place he has created has become hostile and frightening, and he is effectively a prisoner in his own home, as was Beth in ‘The American Lover’, for different reasons, but both out of their control.

Such a lack of control follows in ‘The Housekeeper’, one of two stories in the collection that places a historical literary figure at the centre of the narrative, though not as protagonist. Rather, it is the protagonist who is at their mercy. ‘The Housekeeper’ follows a tryst between Daphne du Maurier and housekeeper Mrs Danowski (or Danni, as du Maurier calls her), who says of herself at the outset, ‘Everybody believes that I am an invented person’. The belief is that Miss du Maurier uses her former lover as the basis for the monstrous Mrs Danvers in her famous novel Rebecca. Subsequently, Mrs Danowski (we never learn her first name) feels a great lack of control over her own life, and thus she recalls her story:

My poor life. I live in Padstow in a rented room, with a view of the sea. I earn a small living from a needlework enterprise. I have a heart full of memory.

We learn that, in her position as housekeeper, she ‘would not normally (or not necessarily) be introduced to the luncheon guests’, but a first meeting of the ‘shadowy’ Miss du Maurier has a significant impact, ‘as though I were the one being called upon to bring her to wholeness’. Mrs Danowski is mesmerised. A sojourn to the summer house leads to a passionate love affair between the two women, which starts with a request from Miss du Maurier that ‘Danni’ sit and stroke her head: ‘I trespass upon dear women friends sometimes, to do this for me … and I have not been alone with a woman for a long time.’

This revelation brings an almost predatory tone to the narrative, and there are reminders of the dominant force in the dynamic: ‘I knew I had to wait. I was Miss du Maurier’s servant.’

The forbidden nature of the affair, their ‘wicked loving’, as Mrs Danowski refers to it, means there’s an expectation that it cannot end well, at least for her. And as she uncovers the nature of Mrs Danvers’ character in Rebecca, she continues to torment herself, believing she ‘will never know the truth’.

In a similar vein, ‘The Jester of Astapovo’ tells the story of stationmaster Ivan Andreyevich Ozolin, a man at the mercy of another literary great: Leo Tolstoy. We learn that Ozolin is a humble man, who says of himself, ‘I think I am nothing’. Early on, he believes he is in love with a woman who is not his wife, but when he is alone with her, he can only sit awkwardly and ridicule his appearance:

“Look at these!” he said with a guffaw. “And look at the little bit of my leg showing between the top of the sock and the bottom of my trousers. How can we take anything seriously – anything in the world – when we catch sight of things like this?”

Count Tolstoy arrives at Ivan’s ‘insignificant’ station, Astapovo, seeking refuge. Ozolin welcomes the writer into his home, giving up his marital bed, to the increasing irritation of his wife, Anna. But Ozolin embraces the responsibility: “My destination is here. I am the guardian of Count Tolstoy’s dying wish.”

Ultimately, the protagonist loses his wife, but so low is his self-esteem that when she does leave his response is to say, “Oh well, I expect Anna’s left because she’s tired of my jokes. I don’t blame her at all.” He cites his own character flaws as valid reasons for her departure. Tremain’s use of a well-known figure acting selfishly – knowingly, or otherwise – at the expense of a humble and less privileged protagonist, is an interesting and original way to examine this aspect of the human condition.

As well as creating such vulnerable, vivid characters, Tremain often uses a ‘plant and payoff’ device to great effect in her stories. ‘A View of Lake Superior in the Fall’ tells the story of Walter and Lena Parker, a couple in their seventies. They ‘run away’ to Lake Superior, to escape their daughter who has moved back into the family home and is dominating with her volatile lifestyle.

Walter took a daily morning dip in the lake before breakfast … It always had been cold but Walter felt that this immersion somehow cleansed his blood and prolonged his life.

This early revelation immediately sets alarm bells ringing in the reader’s mind. The couple go on to endure and survive a bitter winter in their cabin, but, sure enough, Tremain eventually gives us the payoff:

One morning in April, with the sun at last quite high in the sky, Walter went down to the lake and put a toe in the water and decided he’d risk going for a swim.

There follows a touching exchange between husband in water and wife on land. It’s as natural and familiar as conversations can only be in lifelong relationships, but we soon learn that ‘Walter never returned to shore’.

Similarly, in ‘Smithy’, eighty-year-old Reginald Smith takes a daily walk along Blackthorn Lane, having ‘appointed himself the guardian of the lane’. His daily stroll had a purpose, to remove all the rubbish left by other people:

[Smithy] took it home, where he sorted it according to the council’s Recycling Instructions, and then, tired from his walk, he sat down in an old armchair and fell asleep.

When one day Smithy discovers an old, discarded mattress, which leaves him ‘sick and troubled’, a seed is sown. He hatches a plan to shift the mattress, but knowing what we already do about him – his age and need for naps – it seems inevitable that he will falter. And so he does, losing his footing to fall onto the mattress. And it’s cold. Smithy  knows he should try to get up and go home, ‘yet somehow, he didn’t feel inclined to do this’.

knows he should try to get up and go home, ‘yet somehow, he didn’t feel inclined to do this’.

These two stories leave us with a feeling of helplessness and near-frustration on behalf of the doomed protagonists, Walter and Smithy. We silently urge the two men to make a different choice. We care about them and feel saddened by their loss, not just because of their sympathetic character, but also because Tremain touches on something universal that we can empathise with: the frailty that comes with age.

The collection finale, ‘21st-Century Juliet’, brings us as unreliable a narrator as could be devised: the story is told via a series of Juliet’s own diary entries, and she speaks from a position of privilege. Her emotional outpourings report social engagements where ‘Mummy drinks about five litres of champagne’, or she has ‘Dinner at Claridges’. Yet her entries are also tinged with a sense of helplessness, a frequent stream of one-liners: ‘I wanted to fall off the edge of the planet’; ‘Keep bursting into tears’; ‘Feel horribly alone’. Juliet is lonely and we understand, we sympathise. Her family hopes she will enter a loveless marriage to solve the financial crisis they are currently experiencing, and while Juliet refuses the suggestion from the outset, she also records: ‘Then find myself remembering that I’m thirty (shit) and no one has asked me to marry them yet and I’m getting fed up working in PR.’

Juliet is such a product of her upbringing that she is hard-wired to this mindset. We inwardly cheer her as she covertly rebels against expectations for a while, but her helplessness is cemented by the heartbreaking loss of her closest relative and surrogate brother, and she finally takes the decision to enter the financially viable marriage. The story ends on her wedding day: ‘I’m far too thin for my dress. When I get into my dress, it just hangs on me like a shroud.’

Such is the helplessness of this conclusion that it stays with the reader long after the book is closed.

The skilled portrayal of character and setting in such a short form is on display throughout this collection, as is the use of signposts to guide the reader, without ever being clumsy or obvious. Not to mention the sheer scope of subject and theme. The collection is a masterclass from Tremain in the handling of fictional devices.

And so to where my story ends: with a memory and a legacy. In 2014, I jumped at the chance of attending Rose Tremain’s talk at the Cheltenham Literary Festival, having previously only had an intangible sense of her existence through her fictional worlds. It was a sell-out – and I just managed to grab a seat with a restricted view. During the Q&A, for some reason, I threw caution to the wind and asked a question. About process. Ms. Tremain craned her neck to tell me story ideas came to her first, often after reading a snippet or hearing a news item. She said she often turned it round by thinking, “What if…?”

And that’s the legacy. I’ve returned to ‘What if…?’ time and time again as I wrestle with my fledgling short story collection. So, in addition to recommending The American Lover, I also say thank you to Rose Tremain, for the stories I have read, for the stories I will read, and for the stories I hope to write.

~

Janis Lane has a Masters Degree in Creative Writing from Manchester Metropolitan University. She writes fiction and non-fiction, and one of her short stories was longlisted for the 2016 Bath Short Story Award. She is currently reworking her first novel and finishing a novella. Janis lives in Lyme Regis with her busy family, and has built a small summerhouse in the garden to write in peace. She can also be found scribbling in her stationery-cum-literary curios shop, The Writing Room. She blogs at writingroomlyme.com/blog and tweets @WritingRoomLyme. Photo © Nick Ivins.

Janis Lane has a Masters Degree in Creative Writing from Manchester Metropolitan University. She writes fiction and non-fiction, and one of her short stories was longlisted for the 2016 Bath Short Story Award. She is currently reworking her first novel and finishing a novella. Janis lives in Lyme Regis with her busy family, and has built a small summerhouse in the garden to write in peace. She can also be found scribbling in her stationery-cum-literary curios shop, The Writing Room. She blogs at writingroomlyme.com/blog and tweets @WritingRoomLyme. Photo © Nick Ivins.

~

Image of Rose Tremain © Jerry Bauer

One thought on “Fictional Worlds”

Comments are closed.