('Welcome to Tennessee' © Aaron Webb, 2008)

*

In this essay, shortlisted for the 2017 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Richard Newton recommends Cormac McCarthy as a short story writer, whether he likes it or not.

~

Comments from the judging panel:

‘This essay reads with gusto and daring. As a whole, it challenges our sense of where short stories and novels, as literary forms, agree to differ. It reminds us that it is only the force of a story – to reveal what is true about the human condition – that matters in the end. The author gives us a good, sharp sense of the stark and gritty honesty of McCarthy as a writer, and the axe-blade sharpness of his prose.’

‘A lively and well-written piece.’

‘Fun and persuasive.’

‘Written in suitably bad-ass prose.’

~

Richard Newton was born in Sunderland, UK, and grew up in Africa. After an early career in environmental education and a stint as a wildlife officer in Malawi, he has been a freelance writer since 1989. He has won awards for both fiction and non-fiction, including the 2015 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition. He and his wife currently live in Spain.

~

~

CORMAC McCARTHY, WHETHER HE LIKES IT OR NOT

by RICHARD NEWTON

~

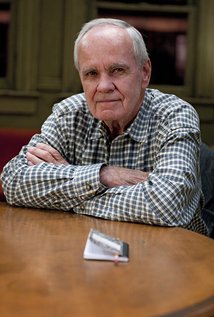

Ride him down, bring him in. Against his will, if that’s what it takes. Drag him to the pantheon kicking and writhing. Disregard his testimony: ‘I’m not interested in writing short stories. Anything that doesn’t take years of your life and drive you to suicide hardly seems worth doing.’ Commit Cormac McCarthy to the front rank of short story writers; to hell with his protestations.

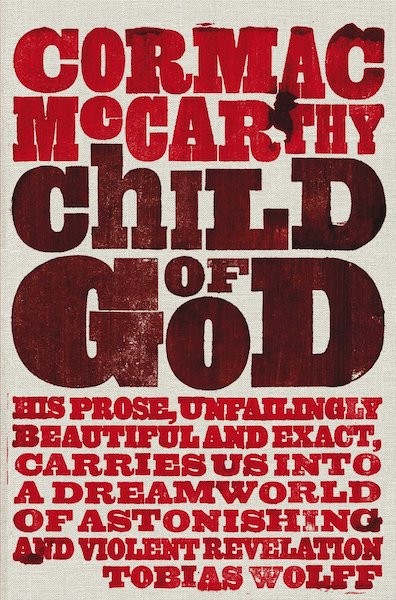

The case centres on Child of God. A novel? That’s his defence. Sure, it’s arranged chronologically, threaded with a common narrative. But rearrange the constituent parts – or isolate them; or present them as is – and this supposed novel subverts into so many short stories. Take your pick.

There is a proviso. The ‘novel’, such as it is, involves scenes of violence, a surfeit of rape, and – let’s not beat around the bush – instances of necrophilia. Extract a close-to-the-bone constituent part and the validity of the core assertion is destabilised by, well, revulsion. The proviso, therefore, is: approach with caution. If we can do that, there is a viable argument that we have here some of the finest of all American short stories.

What is a short story? That matter could divert us for the duration, so let’s agree that brevity is the defining quality, and that economy of length should not be at the expense of completeness. In general, the rules drummed into us in the classroom – beginning, middle, end – apply. (There are experimental exceptions, but that’s not the case here.) The ideal is something short and complete, written in frugal prose.

Cormac McCarthy is frugal by style, sentence by sentence, page by page. Dip into any of his books and spare a thought for his editor. Where’s the authorial indulgence? Where’s the flab? From manuscript to publication, there is none. ‘[His] prose is as clean and hard as pebbles,’ stated British novelist Gordon Burn, in an Independent on Sunday review for All the Pretty Horses.

So let’s dip in. From the off, we’re immersed in an unforgiving landscape. The backdrop is weather-worn, the voices authentic. It doesn’t take long to establish that we’re in rural America: Sevierville, Tennessee. Exactly when is a trickier issue. These pieces are infused with the imagery and sensibilities of a past age. Remote homesteads, guns, horses, sheriffs. The occasional references to automobiles, or microphones, or other such, jar deliberately.

So let’s dip in. From the off, we’re immersed in an unforgiving landscape. The backdrop is weather-worn, the voices authentic. It doesn’t take long to establish that we’re in rural America: Sevierville, Tennessee. Exactly when is a trickier issue. These pieces are infused with the imagery and sensibilities of a past age. Remote homesteads, guns, horses, sheriffs. The occasional references to automobiles, or microphones, or other such, jar deliberately.

In the vast spaces between major cities and highways, the advance of modernity is slow and piecemeal. The episodes described here are largely set in the 1950s, and were written in the early 1970s. Yet some of the nineteenth century cultural throwbacks evoked by McCarthy persist to this day in the tight-knit, God-fearing, gun-loving communities of the American boondocks.

Child of God is divided into three parts, each part subdivided into chapters, most in the third-person point of view, some in the first. Almost any chapter we separate out (with the proviso in mind) will do the job. For instance, page 21 in the paperback (Picador, 1989, my own mightily thumbed copy): ‘I don’t know. They say he never was right after his daddy killed hisself. They was just the one boy. The mother had run off, I don’t know where to nor who with.’

This chapter, this segment – this short story – hits the scales at a shade under three hundred words. After introducing the boy whose daddy ‘killed hisself’, it lingers, with characteristic McCarthy unsentimentality, on the aftermath of the daddy’s suicide by hanging.

The old man’s eyes were run out on stems like a crawfish and his tongue blacker’n a chow dog’s. I wisht if a man wanted to hang hisself he’d do it with poison or something so folks wouldn’t have to see such a thing as that.

There follows a digression about “old Gresham”, who went crazy when his wife died and sang “the chickenshit blues” over her open grave. The pay-off brings us back to the boy, and names him: ‘But he wasn’t a patch on Lester Ballard for crazy.’

Lester Ballard. If we follow the prescribed narrative order he will be revealed to us incrementally. But in the flow of real life, our judgements of strangers must be made without curated divulgence. Would we spot a bad ’un in time?

Page 61:

Ballard among the fairgoers stepping gingerly through the mud. Down sawdust lanes among the pitchtents and lights and cones of cottoncandy and past painted stalls with tiers of prizes and dolls and animals dangling from guyropes.

He partakes of the usual fairground challenges. He cheats while fishing for numbered, celluloid fish, turning them over against the net, discarding them if they don’t match the winning numbers. Alerted by a female customer, the attendant curtails his go. ‘I might not be done playin, said Ballard. And then again you might, said the attendant.’

As Ballard passes the woman who thwarted his efforts, he says: ‘You a busynosed whore, ain’t ye?’

The fairground story is a gaudy, animated slice of Americana. As the atmosphere swirls and buffets around us, our attention remains fixed on Ballard. Lured by rifle fire, he weaves through the throng to the shooting gallery.

He pays with coins and shoots at the dangling target cards. He’s a natural deadeye, and ultimately walks away with three stuffed toys; the maximum permitted haul of grand prizes. Fireworks paint the night sky. Among the crowd, he singles out a young girl.

In the flood of this breaking brimstone galaxy she saw the man with the bears watching her and she edged closer to the girl by her side and brushed her hair with two fingers quickly.

And there it ends, unsettlingly. Five pages, 1,200 words, near enough. A perfectly formed short story with that rarest of merits: it radiates beyond its limits. There is much more here than is set down on paper. We’ve picked up on it. Hopefully the young girl will, too.

Let’s encounter Ballard again, as for the first time. This story is my favourite, not just of this collection but quite possibly of all time. Folded at the corner for instant access, page 70:

In the smith’s shop dim and near lightless save for the faint glow at the far end where the forge fire smoldered and the smith in silhouette hulked above some work. Ballard in the door with a rusty axehead he’d found.

Ballard asks the blacksmith to sharpen the blade. The smith has misgivings. The axe has gotten ‘stobby’ and has no handle. A new one would be better value. But Ballard presses, and the smith accepts the challenge.

For five pages, he lovingly talks the process through, sharing the secrets of the trade with his taciturn customer. ‘Not too fast, said the smith. Slow. That’s how ye heat. Watch ye colors. If she chance to get white she’s ruint. There she comes now.’

He hammers the blade on the anvil, returns it to the heat, all the while providing commentary. Finally the stobby blade is sharp and gleaming.

It’s like a lot of things, said the smith. Do the least part of it wrong and ye’d just as well do it all wrong. He was sorting through handles in a barrel. Reckon you could do it now from watchin? he said.

Do what, said Ballard.

Two people on entirely different wavelengths. Ballard’s disinterest is ominous.

He’s more at ease among people he knows, such as the dumpkeeper, who recurs in the sequence. In the story starting on page 25, common prejudices about the American backwoods are affirmed: ‘The dumpkeeper has spawned nine daughters and named them out of an old medical dictionary gleaned from the rubbish he picked … Urethra, Cerebella, Hernia Sue.’

The humour is hollow. As pure syllables, those are pretty names. Who are we to belittle them? McCarthy rubs our noses in a world that may be simple, outdated, and lacking education, but is nonetheless genuine. These are people who exist on their own terms. So chuckle if you wish, but do so on the understanding that McCarthy isn’t a writer who resorts to easy laughs (or, when depravity bursts forth, moral judgement). He’s a neutral observer.

From page 110, he positions us to eavesdrop a conversation between Ballard and the dumpkeeper. The dumpkeeper says:

You ort to be proud, Lester, that you ain’t never married. It is a grief and a heartache and they ain’t no reward in it atall. You just raise enemies in ye own house to grow up and cuss ye.

Even in company, Lester Ballard has the hallmarks of a loner. He’s a world unto himself. Witness the story beginning on page 96. Again, imagine crossing paths with him for the first time: Ballard shopping. ‘Before a dry goods store where in the window a crude wood manikin headless and mounted on a pole wore a blowsy red dress.’

Even in company, Lester Ballard has the hallmarks of a loner. He’s a world unto himself. Witness the story beginning on page 96. Again, imagine crossing paths with him for the first time: Ballard shopping. ‘Before a dry goods store where in the window a crude wood manikin headless and mounted on a pole wore a blowsy red dress.’

He goes in. After some hesitation with the salesgirl, he checks the price of the blowsy red dress. He says he doesn’t know the size of the girl it’s for, though he estimates she’s smaller than the salesgirl. He requests some drawers, too, and blushes at that.

Purchases in hand, he progresses to Fox’s store for cans of beans and sausages. ‘What about that boy they found up here yesterday evenin? Mr Fox said. What about him, said Ballard.’

On that note the story ends. Reading in sequence, yes, we’d know that Ballard killed the boy and his girl, and that the girl’s body is currently strung up in his attic. That’s who he has been shopping for. But even without that knowledge, there is something unsettling about this story, something that doesn’t add up. As before, as again, it expands beyond its limits.

So to the nub. It can’t be avoided indefinitely. Lester Ballard is a serial killer and a necrophiliac. In some stories his actions are described, in others they’re elided. Let’s opt for a tamer example, from the story starting on page 115:

She was lying in the floor but she was not dead. She was moving. She seemed to be trying to get up. A thin stream of blood ran across the yellow linoleum rug and seeped away darkly in the wood of the floor. Ballard gripped the rifle and watched her. Die, goddamn you, he said. She did.

This story (and several others) would not sit politely in an anthology. Child of God is not a comfort read. McCarthy plumbs the depths of life beyond the drop-off of civilisation. Though the entire book weighs in at under two hundred pages, reading from cover to cover is a test of endurance, and of one’s moral compass.

By breaking it up, it becomes manageable, though – as we struggle with occasional scenes of depravity – we face a quite separate ethical quandary. Do we have the right to deconstruct an intended novel into a collection of short stories?

Of course we do.

Fiction is the ultimate conceptual art. Words are nothing without the reader’s imaginative power. We invest the printed descriptions with our own visualisations. Few of us have firsthand knowledge of Sevierville and its environs in the 1950s. And surely – hopefully – none of us have been touched by anything remotely like the crimes portrayed.

Yet, as with any fiction, the writer’s inventions depend on us, the readers. When a work of fiction is dispatched to the world, we can’t be told how we should interpret it, or even the order in which it should be read. And if we choose to regard it as something other than a novel, well that’s our prerogative.

So I hereby formally contend that Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God is an outstanding collection of short stories, and propose that we bring him in to be pelted with plaudits. Whether he likes it or not.