by Mike Smith

I recently treated myself to an ostentatiously bound copy of O. Henry’s 101 Stories, and discovered from the introduction within that he shared two out of three of his real names with my adoptive grandfather, on the distaff side. This alone would have been sufficient to endear him to me. There was also the fact that he came from a town in North Carolina with which, on several occasions, I have confused a town in South Carolina, in which I have friends. The coincidences go on. I myself have adopted an American voice, for the telling of some stories but in my case it was in pursuance of a robust narrative voice, and in avoidance of that class categorisation, with the attendant despising, that is said to follow when any English voice opens its mouth within earshot of any English ear.

O. Henry’s stories are in the main short, and his voice, seems to me, as a rank outsider, to be entirely authentic. His stories are forceful, tricky, knowing, and observant, and have in them a greater subtlety than might at first be apparent. There is too a tenderness and sensitivity, to the losses and injuries that the human condition inflicts upon those of us blessed with it, which the brash exterior of his prose cannot quite conceal.

O. Henry’s stories are in the main short, and his voice, seems to me, as a rank outsider, to be entirely authentic. His stories are forceful, tricky, knowing, and observant, and have in them a greater subtlety than might at first be apparent. There is too a tenderness and sensitivity, to the losses and injuries that the human condition inflicts upon those of us blessed with it, which the brash exterior of his prose cannot quite conceal.

As one who labours in the gardens of a Hotel with a Michelin starred restaurant, I can vouch for the credibility of O. Henry’s Bogle’s Chop House, and for that of the more upmarket address to which Mr Towers Charlton takes his unexpected date. As for that un-ransomed brat, Red Chief, he has been well enough drawn to be copied, if I am not mistaken, by at least two Hollywood movies, albeit in heavy disguise.

O. Henry’s narrative voice is one that you do not listen to in the hushed respectability of the Russian Doctor’s consulting room, nor in the whisky sodden darkness of the American adventurer’s bar. It is not a voice that would grace the opulence of the gentleman’s club, nor seem at home in the public house of the English rural yeoman. It is a voice that you would hear across the table of a New York eating house, above the hubbub of other diners, while you yourself tucked into a plate of ham and eggs, or a dish of Boston beans. His grip on that voice is as strong as his grip on the language itself, which he twists and turns into extended metaphors and oblique asides. In stories like The Furnished Room there is a whiff of Gothic Horror, and in The Gift of the Magi, he wades through sentimentality to produce a Christmas Story that has become almost iconic. The Unfinished Story frames with pure fantasy a hard-nosed exposé of the brutal economic and social mores of his time and, human nature not having given ground in the intervening years, of our own. And if Twenty Years After, with it’s cool bluff, is anything to go by, O, if I may call him that, would have played a mean poker hand.

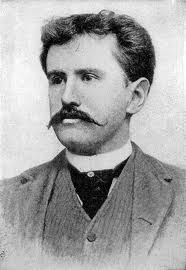

O. Henry was born in 1862 and died in 1910. He squeezed into, or out of the last dozen years of his life, around three hundred stories, which according to my introductory informant, he was able to sell for ‘tall prices’. His apprenticeship in this endeavour, was served, along with time, in the Ohio Federal Penitentiary, in which he was incarcerated for embezzlement. I cannot help but think that both the location, and the indictment were suitable ancestors of the storyteller’s art that they begat.

101 Stories, by O. Henry, has been variously published, including in an edition by The Folio Society of London, in 2002.

Mike Smith writes across a range of genres, including poetry, drama, and literary criticism. Under the name Brindley Hallam Dennis he has just published That’s What Ya Get! Kowalski’s Assertions. In 2009 he received the degree of M Litt from Glasgow University. He currently teaches Creative Writing at Cumbria University. His writing has been published, broadcast and performed, and has won prizes and awards in Scotland and England. He is particularly interested in the structure of short stories, and in the relationship between the story and the narrator.

Read: