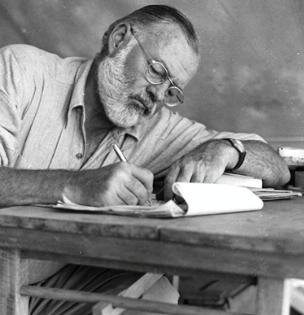

photo by Danny Wolpert

Ernest Hemingway‘s ‘A Clean, Well-Lighted Place’

by Jason Clifton

I realise that, for some, selecting this short story by Hemingway may seem too obvious a choice. “Why not a more obscure short story, something we haven’t heard of?” you might ask. The thought crossed my mind too. There are countless excellent short stories less known to the general reader and, after all, Hemingway is acknowledged as a ‘master’ of the short story, and has been for more than seventy-five years.

Though critics have, over time, taken issue with Hemingway’s perspective, particularly in relation to gender studies, very few would argue his skill as a prose stylist and storyteller. In that regard he has remained undefeated, the champ – faring a lot better than the boxers in his own short stories. He made his name as a writer with the short story form, with the story collection In Our Time, first published in 1924, two years before his breakthrough novel The Sun Also Rises. There were other short story collections in his youth – Men Without Women, published in 1927, and Winner Take Nothing in 1933, where ‘A Clean, Well-Lighted Place’ was first published.

For many, myself included – and I have read and enjoyed, to one degree or another, all of Hemingway’s novels – it is the short stories, out of all his works, that remain the most memorable. ‘Memorable’ is a word that is used a fair bit by literary reviewers – or that once you’ve read it, you ‘won’t ever forget it’. But, be honest, how many short stories do you genuinely remember anything of two or three months after reading them, let alone two or three years afterwards? Very few, I would bet.

For many, myself included – and I have read and enjoyed, to one degree or another, all of Hemingway’s novels – it is the short stories, out of all his works, that remain the most memorable. ‘Memorable’ is a word that is used a fair bit by literary reviewers – or that once you’ve read it, you ‘won’t ever forget it’. But, be honest, how many short stories do you genuinely remember anything of two or three months after reading them, let alone two or three years afterwards? Very few, I would bet.

This is not a fair test of the quality of a short story. For most of us, there are a lot of things, here in reality, vying for space in our memory – from where we put our house keys, to the birthdays of our family members. Or, to be more serious, significant memories such as those of friends or family members who have died, or those key moments, now barely remembered, that set us on a particular course in life or shaped our values and beliefs. It’s not surprising, then, that we don’t have a great memory for all the details or turns of plot in a piece of fiction, though we may certainly remember whether or not we enjoyed them.

So it is for the simple, but significant, quality of ‘memorability’ that I selected Hemingway’s short story ‘A Clean, Well-Lighted Place’ for discussion. I first read Hemingway as a teenager for my own pleasure, and then in my twenties I wrote my final dissertation on him for a degree in American Literature. I have picked up the stories from time to time, collected in The First Forty-Nine Stories, and read them in the decade or more since.

I have chosen this story over the other forty-eight stories, because I think it speaks to us beyond its own time. It speaks in a way that is more relevant, and more profound, than some of the other celebrated short stories by Hemingway, such as ‘The Snows of Kilimanjaro’, ‘The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber’, or even those two stories so beloved of many creative writing tutors, ‘Cat in the Rain’ and ‘The Killers’.

The scenario is simple. It is ‘very late’, and two waiters working in a Spanish café are watching their only customer of the evening, an old man who is completely deaf. He is a regular and a ‘good client’, but the waiters know from experience that if he gets too drunk he may leave without paying, so they keep an eye on him. Neither the old man nor the two waiters are given names in the story, which contributes to the sense that we are witnessing ordinary people in an ordinary scenario, as opposed to Hemingway’s more sophisticated and delineated (and therefore distanced) characters in more exotic scenarios, like the well travelled writer Harry in ‘The Snows of Kilimanjaro’. Though ‘A Clean, Well-Lighted Place’ begins by focussing on the old man, he says no more than two words in the course of the story: ‘Another brandy’.

The conflict of the story is between the two waiters – one young, one older. Though ages are not given in the text, it seems (from their dialogue) that one waiter is around twenty-five while the other is closer to forty, and their conflict develops from their opposing attitudes to the old man they are attending. The young waiter opens a conversation with the older waiter by telling him that the old man recently tried to commit suicide. He tried to hang himself, but his niece found him and cut him down, ‘For fear for his soul’.

The conflict of the story is between the two waiters – one young, one older. Though ages are not given in the text, it seems (from their dialogue) that one waiter is around twenty-five while the other is closer to forty, and their conflict develops from their opposing attitudes to the old man they are attending. The young waiter opens a conversation with the older waiter by telling him that the old man recently tried to commit suicide. He tried to hang himself, but his niece found him and cut him down, ‘For fear for his soul’.

The younger waiter, however, is just making conversation. He couldn’t care less, and is simply annoyed that this deaf old man won’t leave the café so that he can close, go home and sleep with his wife (the suggestion is that they have a good sex life). He pours the old man’s last brandy over the brim as a kind of gesture of his irritation and, though the old man can’t hear him, he says, ‘You should have killed yourself last week’.

Hemingway briefly adds, ‘He did not wish to be unjust. He was only in a hurry’. It’s possible that the young waiter has a better side to his nature, yet one feels his attitude and behaviour here reflects the brusque and unfeeling individualism that permeates many of our modern social experiences.

By contrast, the older waiter is sympathetic to the old man, or perhaps it is more a case of empathy. The difference strains the conversation between the two waiters, who appear to be of equal rank and therefore free to speak their minds. But the need for professional courtesy restrains both waiters from open argument, and, at first glance, that restraint makes the conflict appear so subtle that at the story may seem purely observational rather than dramatic.

‘I am of those who like to stay late at the café,’ the older waiter finally says. He empathises with the old man because, like him and many others, he needs a clean, well-lighted place to escape his own feelings of despair, and the darkness, both literal and metaphorical. That phrase ‘a clean, well-lighted place’ does not refer to any place that might be open with a drink to be had and some kind of human presence. For example, when the older waiter goes to a bar to have a drink, after they have closed the café,he finds himself in a bar that does not have the same calmness, dignity or charm as his own. He cannot linger over ‘…the shadow the leaves of the tree made in the electric light’.

In the story, the bodegas and bars that are open all night are there to make money, not to provide a refuge of calm and dignity for the lone man or woman with trouble on their mind. They cater to the majority of people who, at this time of night, want to drink, listen to music, laugh and talk loudly, and perhaps seduce or be seduced by a stranger, much like the nightclubs and late-night bars in our own time. These customers don’t particularly care if the place is clean or well-lighted, or if there is an attractive shadow being cast by the play of light on the leaves of a tree outside.

In the story, the bodegas and bars that are open all night are there to make money, not to provide a refuge of calm and dignity for the lone man or woman with trouble on their mind. They cater to the majority of people who, at this time of night, want to drink, listen to music, laugh and talk loudly, and perhaps seduce or be seduced by a stranger, much like the nightclubs and late-night bars in our own time. These customers don’t particularly care if the place is clean or well-lighted, or if there is an attractive shadow being cast by the play of light on the leaves of a tree outside.

This story reflects the limitations of our contemporary world with its billboard promises of lightness, comfort and companionship. It offers an understated critque of modern capitalist society even as it evokes for us Spanish life before their Civil War. As long as you have the price of a drink or two about you, ‘free choice’ is yours, although the needs of the human soul, Hemingway suggests, are unlikely to be served.