photo © Chris Hoare, 2008

by Susmita Bhattacharya

‘I wanted real adventures to happen to myself. But real adventures, I reflected, do not happen to people who remain at home: they must be sought abroad.’

~ James Joyce, Dubliners

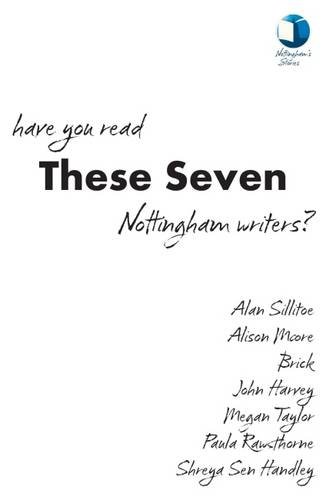

This is so true, and, as writers, we seek the unknown. Exotic places, far away from our daily humdrum lives. The thrill of adventure, and soul searching. But the anthology These Seven remains firmly rooted to its home town: Nottingham. It is a unique exercise in delving into the everyday lives of people in this city, making Nottingham sparkle and breathe and come to life.

One would imagine that the stories would be similar, all sharing the same setting as they do, but each one couldn’t be more different from the rest. This anthology is well-rounded and explores themes and characters in the city of Nottingham through the points of view of its myriad citizens. At the same time, we also get a sense of the city seen through the eyes of its people, as well as the different angles the writers have focused on.

Families, children and security play big roles in this anthology. In ‘Here We Are Again’ by Megan Taylor, we see the city through a young mother’s eyes. She’s returned home to meet her first love and now looks for the comfort of familiarity in the buildings and people around her.

The tram tracks flare, and there’s more light glittering from the paving stones ahead; the concrete looks woven through with tinsel. Even the old domed council building shines: a creamy glow to its stone column and lions.

She, who has been an outsider in so many ways, is waiting to be accepted by her loved ones, especially by her lesbian lover.

Paula Rawsthorne’s story, ‘A Foreign Land’, depicts the tale of a real outsider: an asylum seeker. A young boy, Jamal – or Jay, as he’d rather be called – is caught up in the nasty experience of deportation to a country he doesn’t know. His ‘homeland’, Sudan, is the place where he is an outsider, not Nottingham, where his school and his best friend Eddie are, and where he supports the Reds. The story raises the question, which is a foreign land for this immigrant boy: his country of origin, or the place where he resides with his family? While we see a soft, almost feminine side of Nottingham in ‘Here We Are Again’, in ‘A Foreign Land’ we are placed in the rough areas of the city. There is danger, hardness and, even though it is England, it doesn’t sound very different from the country the family has escaped from to find safety. Life is still a struggle and, though Jay’s parents are educated people and had respectable jobs back in Sudan, they are not recognised for their worth here.

There are some kids from my school live here but none of them are my good mates. My real mates aren’t allowed to come to mine. They say that their mums say the Tower Estate is too rough. But that’s better, because, to be honest, I don’t want them seeing what a dump I live in and it means that I can tell them that I’ve got an X-box and they’ll never know I am lying, so it works out okay, really.

In Brick’s brilliant graphic story ‘Simone the Stylite’, as we walk through Nottingham with Simone, we take in the sights, the people, the busyness of a city, and this all enhances Simone’s loneliness, her quest for a quiet space. She finds her place of rest on top of the  sixty-metre-tall sculpture ‘Aspire’, in the university campus, and there she resides, year after year, doing what she loves: being alone. It is a satirical piece on modern-day living. How busy life is, how little time there is for looking inwards, meditating even. Through the pen and ink drawing medium, we are treated to Nottingham’s familiar grand buildings and the university campus, housing the Aspire Tower.

sixty-metre-tall sculpture ‘Aspire’, in the university campus, and there she resides, year after year, doing what she loves: being alone. It is a satirical piece on modern-day living. How busy life is, how little time there is for looking inwards, meditating even. Through the pen and ink drawing medium, we are treated to Nottingham’s familiar grand buildings and the university campus, housing the Aspire Tower.

But writing about the familiar can also be pushed to the boundaries to explore realms of magic realism, or fairy tale-like depictions. ‘Hardanger’ by Alison Moore is the only story in the collection not set in Nottingham, and it hovers, dream-like, in the world of hallucinations or make-believe. Sue, the young protagonist, is trying to adjust to change: a new stepfather, new city, new house. In this time of transition, she finds a boyfriend, Travis, who hovers around, existing and, yet, not really there. ‘There was a boy, a disarmingly beautiful boy, who never quite made eye contact. He came to the house and hung around, or else he took Sue out.’

When the family decide to go on holiday to Norway, Sue doesn’t want to go. By way of persuasion, her parents ask if she would like to invite Travis to join them. Moore’s descriptions of places, especially water, casts an eerie feeling to the piece. Water is a living thing, with a mind of its own; a warning about what is to come later.

Marlene saw a field, grey beneath the stormy sky, a wide expanse of long, dense grass rippling in the wind. Then she saw that the whole field was shifting; it was rising and falling like something alive, and she realised that it wasn’t a field at all, but water, the river Plym.

Other-worldly connections are also explored in Shreya Sen Handley’s story ‘Nimmi’s Wall’. This story is set in the wealthier parts of Nottingham, in a big house with a mysterious garden. Nimmi is a new arrival from ‘sweltering Kolkata’ to cold, dark Nottingham. Her marriage too is cold and loveless; her husband though an affluent surgeon, has little respect for her or her needs. We get to go into the city’s past as Nimmi researches the history of the wall at the bottom of her garden.

What she really liked doing was piecing together what she could about this beautiful garden she had acquired so serendipitously. From the Doomsday Book of 1086, to medieval references to walled orchards at the heart of Sherwood Forest, to newspaper reports of Byronic duelling on the same spot several centuries ago, she traced the history of her wall…

There is an element of mystery as Nimmi encounters people, a settlement, at the bottom of the garden. Are they real or a figment of her imagination? Does she crave human company so much that she starts interacting with imaginary people, or are they a living testimony of the history of the wall? Like ‘Hardanger’, we have elements of danger and magic-realism woven together to create a fantastical Nottingham.

The two stories that bookend the anthology are similar in the fact that they are about ex-offenders, the law and consequences. ‘Ask Me Now’ by John Harvey opens the book and follows the life of a detective sergeant in the Public Protection Team. The last story is by the late Alan Sillitoe, son of the soil of Nottingham. ‘A Time to Keep’ is set at the time when the M1, England’s first motorway, was being built. Martin’s cousin is part of the construction force and, even though an ex-offender, he is looked upon as being successful. But young Martin wants more in life. He wants to rise above the middle-class and be educated and well read. He reads incessantly, hoping to absorb all the knowledge through osmosis.

Most of the books had been stolen. None had been read from end to end. When opened they reeked of damp from bookshop shelves. Or they stank from years of storage among plant pots and parlour soot.

It is a coming-of-age story where a young boy looks up to his ex-offender cousin, who is all bravado and brash. But certain events lead to Martin ending up being in control and finally believing in himself, that he can make a difference.

“I’m glad you came to work with me today, any road up, our Martin. I wouldn’t have liked to drive home on my own after that little lot” … Martin never thought he’d feel sorry for Raymond, but he did now. He felt more equal than he had ever done – and even more than that.

Though Sillitoe himself hated being termed as ‘the angry young man’ of the 1950s, this story very much addresses the class system and the work ethics of the time.

This wonderful anthology is quite unique in the way that its main setting is the city of Nottingham – it celebrates the city, its people and its stories. The project, initiated by the UNESCO bid process and part of the Nottingham Big City Read initiative, was an ambitious way to connect the readers and established writers of Nottingham, and inspire more writing in the city. The subject is a comfortable place for the writers, like a second skin, and it shows through their stories, so different and yet so firmly placed within the throbbing heartbeats of Nottingham. One does not have to go far to seek real adventures. As you can see, they can be found at home too.

~

Susmita Bhattacharya is from Mumbai, India. She received an MA in Creative Writing from Cardiff University. Her debut novel, The Normal State of Mind (Parthian), was published in March 2015. Her short stories have appeared in several literary journals in the UK and internationally, on BBC Radio 4, and have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She lives in Plymouth with her husband and two daughters, and facilitates creative writing in the community. She blogs at susmita-bhattacharya.blogspot.co.uk

Susmita Bhattacharya is from Mumbai, India. She received an MA in Creative Writing from Cardiff University. Her debut novel, The Normal State of Mind (Parthian), was published in March 2015. Her short stories have appeared in several literary journals in the UK and internationally, on BBC Radio 4, and have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She lives in Plymouth with her husband and two daughters, and facilitates creative writing in the community. She blogs at susmita-bhattacharya.blogspot.co.uk