Image by Laurin Kofler

~

An extract from the introduction to

The Postcolonial Short Story: Contemporary Essays

Maggie Awadalla and Paul March-Russell (eds.)

~

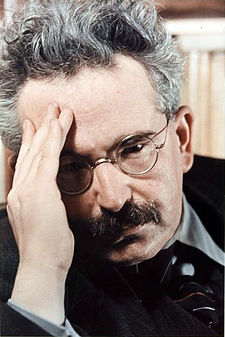

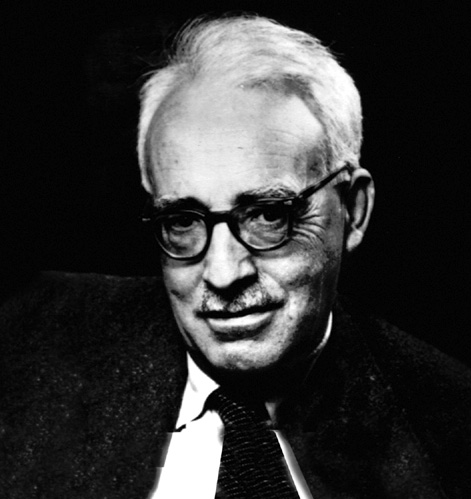

In a society that Walter Benjamin correctly sees as driven by “the secular productive forces of history” (86), this resistance to being either high or low culture has determined the short story’s relatively marginal position to that of the novel. Marginality could, if we follow Benjamin’s associate Theodor Adorno, be recuperated in the form of a negative dialectic – the value of the short story arises from what it is not – but this move would only privilege those short stories that most appropriately fit with Adorno’s conception of the avant-garde (Baudelaire, Beckett, Kafka). The short story, instead, exists within the “torn halves” of art and culture (Adorno and Benjamin 130), and it is this liminal position that produces a form rich in both tension and possibility. Nadine Gordimer hints at something of its measure when she describes the short story as “a fragmented and restless form” (Gordimer 265). Not a fragment of something larger but complete in itself: striven with its own fault-lines.

…a fragmented and restless form.

Adrian Hunter has recently proposed the possibility of reading the short story in terms of, what Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari have called, “minor literature” (Hunter 219-38). They define minor literature as “that which a minority constructs within a major language”. It consists of three elements: “deterritorialization”, whereby language is displaced and contorted by the pressure of colonisation; politicisation, whereby the limited spaces in which language can operate means that it connects “immediately to politics”; and, lastly, “collective value” whereby, since “the political domain has contaminated every statement”, all expressions of the minor culture “already constitutes a common action” that permits “the conception of something other than a literature of masters”. In emphasising the “strange and minor uses” to which the major language is put, Deleuze and Guattari propose minor literature as a type of bricolage that works upon the remains of the dominant culture (16-7). De- and reterritorialization are consequently simultaneous processes in which their very parameters are constantly being re-thought.

The short story becomes a site in which

these tensions can be played out…

Although derived from postmodern theory, the concept of minor literature is highly suggestive for rethinking the liminal, open-ended and fragmented form of the short story. Until now, though, it has had more application within postcolonial studies. Consequently, minor literature is one of the frameworks by which the short story and the postcolonial could be read together. (There are other possible approaches and these are discussed elsewhere in the collection.) For example, the emphasis upon orality that Pratt sees in the work of Mexican, African-American and Afro-Caribbean short story writers can, at least partially, be explained in terms of minor literature (108). Benjamin’s Eurocentric account, accentuated by its historical and ideological contexts, tends towards pathos by presenting as universal the displacement of traditional communal structures – which supported the rituals of storytelling – by the economic forces of industralisation, urbanisation and secularisation. In developing and postcolonial nations, patterns of economic and technological development have been far less clear (even) than in the Western capitalist model. The sharp divides between rich and poor, between the city and the country, and in literacy and mortality, which have undercut the independence movements since 1945, have also meant that oral and performance cultures have endured within the making of postcolonial literature. Orality becomes a resource for North African and Afro-Caribbean writers (see, for example, the respective chapters by Caroline Rooney and Lee Bessette) to shadow the importation of Western modernity into indigenous cultures: to counter the demise that Benjamin tends to see as inevitable. The short story becomes a site in which these tensions can be played out rather than subsumed or hypothetically resolved as melancholic pathos.

Orality plays a part, too, in the form of memory and anecdote within the exiled imagination. The disappearance of communal and intergenerational ties, which Benjamin regards as melancholically beautiful, is for the former colonial subject, whose social condition has often been represented as grotesque or sublime, intensely political. The fact of diaspora, to which can also be added the fact of globalisation, mean that memory inexorably becomes a political act as seen, for instance, in the chapters by Antara Chatterjee, M. Catherine Jonet and Paul March-Russell. The displacement of communities, either by enforced or voluntary migration, complicates Frank O’Connor’s thesis in The Lonely Voice (1963) that the short story thrives in transitional societies, whose foundations are not yet established, so that the voices of submerged populations have an opportunity in which to be heard. O’Connor’s study, which is imbued with a melancholy similar to that of Benjamin’s essay, turns upon a relatively unsophisticated account of community and historical development that Michelle Keown takes to task in her reading of the New Zealand writer, Patricia Grace, and her successors. Like Keown, Alex Padamsee registers language (in this instance Urdu) as a key factor to which O’Connor fails to give due emphasis, but which Padamsee shows to be integral to the undecidability of partition and its historical aftermath for India and Pakistan. At the same time, the comparative studies by Keown, Ailsa Cox and Philip Holden suggest communities of writers, who not only celebrate the particularities of geographical space, but whose inter-generational dialogue also overlaps the borders of history, language and location.

…the short story concentrates upon “the small

fragments of the large fresco”…

A dialectic that emerges around the notion of community may help to explain the current collection’s emphasis upon women’s writing as opposed to Benjamin’s exclusively male account or O’Connor’s misguided critique of Katherine Mansfield. Women are central, even as they are marginalised, to the independence movements due to their biological and social functions. Their paradoxical and ambiguous place within colonial and post-colonial society renders their lives suitable subject-matter for the short story. Furthermore, their stories complement Sabry Hafez’s observation that the short story concentrates upon “the small fragments of the large fresco” (38) rather than the panoramic view that tends to be the proper business of the novel. Women’s writing sits awkwardly in relation to the political act of nation-building and postcolonial literature’s attempt to describe, what Fredric Jameson once controversially termed, the national allegory (65-88). The tendency instead, as Jonet’s study of lesbian short fiction from the Caribbean argues, is towards the interstitial. Yet, it is here that the short story is also found to be at its most political, and most open to the needs of men and women, for example, in Barbara Cooke’s emphasis upon the distressed body in South African fiction.

It is surprising then that, until recently,

there has been little critical attention paid

to the postcolonial short story…

It is surprising then that, until recently, there has been little critical attention paid to the postcolonial short story with only one previous major collection: Telling Stories: Postcolonial Short Fiction in English (2001), which was marred by the death of its principal editor, Jacqueline Bardolph. Part of the reason may be due to the fact that the short story tends to appear in ephemeral publications: either the mass circulation or little magazine. Yet, these titles have played a substantial role in the development of postcolonial cultures, while a number of them have received academic support, for example, Okike following its founder’s, Chinua Achebe, relocation to Massachusetts; Kunapipi, launched by Anne Rutherford, an Australian academic then working in the Netherlands; and Wasafiri, which was founded at the University of Kent in 1984 and continues to be  edited from within the Open University although published by Routledge. Okike, possibly the most celebrated and certainly one of the most enduring little magazines, was founded in the aftermath of the Biafran War with the intention of sustaining Igbo culture in Nigeria but quickly added to that a Pan-African dimension. In its range and quality of writing, and in its readiness for controversy, Okike is a central text in the history of postcolonial writing from Africa. South African titles by contrast, such as Drum (especially in the second half of the 1950s) and Staffrider in the 1970s and ’80s, are intriguing because of their popular base. Whereas Okike was, to some extent, a product of elite culture, Drum especially was a general interest magazine which, as a consequence, provided an outlet for short fiction. The broad appeal of Drum and Staffrider, itself a riposte to the segregated policies of the apartheid regime, was key to their survival. By comparing the publishing history of all three African magazines, it is possible to describe how the short story survives within the spaces of elite and popular culture, and that this ambiguous existence attests to its political potential. Similarly, magazines such as Bim, Kyk-over-Al, Savacou and Voices are integral to the history of Caribbean literature; both within the region itself and as part of the post-war diaspora (see Donnell). During the past decade, the Caine Prize, which awards African short story writers published in English, has further played an important role in promoting and supporting the genre. Its influential patrons include Wole Soyinka, Nadine Gordimer, J.M. Coetzee and Chinua Achebe. Elsewhere, there exist numerous samizdat publications and increasingly, as Shola Adenekan and Helen Cousins discuss in their chapter, writing on the internet. Yet, what is seriously needed, and which the present volume can only register, is a detailed analysis of the role that magazine culture has played within the development of postcolonial literatures.

edited from within the Open University although published by Routledge. Okike, possibly the most celebrated and certainly one of the most enduring little magazines, was founded in the aftermath of the Biafran War with the intention of sustaining Igbo culture in Nigeria but quickly added to that a Pan-African dimension. In its range and quality of writing, and in its readiness for controversy, Okike is a central text in the history of postcolonial writing from Africa. South African titles by contrast, such as Drum (especially in the second half of the 1950s) and Staffrider in the 1970s and ’80s, are intriguing because of their popular base. Whereas Okike was, to some extent, a product of elite culture, Drum especially was a general interest magazine which, as a consequence, provided an outlet for short fiction. The broad appeal of Drum and Staffrider, itself a riposte to the segregated policies of the apartheid regime, was key to their survival. By comparing the publishing history of all three African magazines, it is possible to describe how the short story survives within the spaces of elite and popular culture, and that this ambiguous existence attests to its political potential. Similarly, magazines such as Bim, Kyk-over-Al, Savacou and Voices are integral to the history of Caribbean literature; both within the region itself and as part of the post-war diaspora (see Donnell). During the past decade, the Caine Prize, which awards African short story writers published in English, has further played an important role in promoting and supporting the genre. Its influential patrons include Wole Soyinka, Nadine Gordimer, J.M. Coetzee and Chinua Achebe. Elsewhere, there exist numerous samizdat publications and increasingly, as Shola Adenekan and Helen Cousins discuss in their chapter, writing on the internet. Yet, what is seriously needed, and which the present volume can only register, is a detailed analysis of the role that magazine culture has played within the development of postcolonial literatures.

~

With thanks to the editors and publishers of The Postcolonial Short Story for allowing us to reprint this extract from the introduction. If you would like to read more, you can purchase a copy of the book here.

~

Paul March-Russell teaches Comparative Literature at the University of Kent. He edits the SF journal, Foundation, and is general editor of the SF Storyworlds series published by Gylphi. His previous short story publications include The Short Story: An Introduction (Edinburgh University Press, 2009) and articles for both Thresholds and Short Fiction in Theory and Practice.