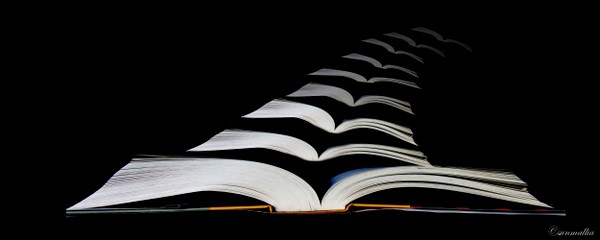

Photo by Paula Mallia

Riptide has been in circulation since 2006. It was a magazine started (and still edited in the main) by writers Ginny Baily and Sally Flint, postgraduate students at Exeter University. I have been involved as a contributor, as an introduction-writer and, most recently, as editor. In other words, I have been around the block a few times, and I have been upstairs as well as down.

The first volume was given a jumpstart by a pilot grant from the Arts Council. Since then, the magazine has pretty much fended for itself, living a hand to mouth existence, yet managing to survive (no mean achievement) and gathering a critical momentum that has ensured that in terms of content, it goes from strength to strength.

(I should add that the Creative Writing department at Exeter have been supportive from the start – Philip Hensher, Andy Brown and Sam North; and through them, we have an office in the English department – any unsuspecting lecturer who goes off on sabbatical is likely to have their room requisitioned and the cardboard boxes moved in – and access to the university’s publicity machine and function rooms for wild Riptide parties.)

Unsolicited submissions begin to pile in as soon as the small flutter of publicity announces another birth (Volume 4 appeared in the autumn of 2009). The typescripts arrive from cities and outposts all over the UK; some from much further afield, garlanded with stamps from Australia, Botswana, Romania, India – and congregate rapidly in large cardboard holding stations. I had not banked on the feeling of déjà vu. For many years, in the last century, I was the person in charge of reading the Faber poetry submissions – the ‘slush pile’ – which, in those days, grew tall as a man and, fast as I managed to chop it down, appeared like a dragon’s tooth to rear up again. (Or like those Thistles of Ted Hughes’: ‘Mown down, it is a feud. Their sons appear/Stiff with weapons, fighting back over the same ground.’) Although at the time I never credited it for my flight from London – a self-imposed exile to a remote and buried corner of England – it occurred to me now that it just might have had a part in it. I realised, in the process of reading through nearly three hundred manuscripts for Riptide, that I was drawing upon a familiar and fairly brutal code of practice:

The covering note first off: the simpler the better. No letters after names – Mr Bob Roy, EKn, reS, TK – no minutiae about short-listings for Ant Hill press or long ago appearances in St Winifred’s school magazine.

But by far the worst sin I unearthed was a new one to the list (it must have crept in over the last ten years): the imperative, ‘enjoy!’

No. No. No. That is like the child-catcher from Chitty Chitty Bang-Bang; the dentist’s ‘open wide’. It made me shut my eyes and count to ten and hope that it would go away, instantly. Likewise manuscripts smelling of Lambert and Butler or dog. Though an editor must try not to be too sensitive: there are bound to be exceptions. I remember a late masterpiece by the aforementioned Ted Hughes being presented in a plastic bag that stank of fish, whose pages continued to stink for weeks after…

I mention these cavils in an attempt to illustrate the level of donkey-work that is required before editing can even begin: there is a great deal of clearing to be done before the wood can be seen for the trees (or is it the other way round?). And I mention it too, not because I expect any sympathy – because I was very pleased to do it once – but to further sing the praises of Ginny Baily and Sally Flint (and all such self-driven editors) who plough on again and again, unpaid, without fuss, without whom the opportunities for short-story writers would be significantly the poorer.

I hasten to say too that there are peculiar rewards to be had from discovering stories among the piles of the unsolicited. Like mining for opals. And I should also make clear that the standard of perhaps fifty per cent of them was worthy of the consideration of two or three or even four different readers.

Now that the magazine is firmly established, and because contacts have been forged with various writers and/or teachers of creative writing, the word can be spread very specifically, and this I found yielded a rich vein of material. I confess that I began with Alison MacLeod, who, as well as offering up the wonderfully disturbing ‘Café Bohemia’, was able to set off a chain reaction that put me at the receiving end of a clutch of stories I would later include and a number of writers whose contributor notes alone reveal them to be the most distinguished collective yet.

For me, the most enjoyable part of the process was the engagement with writers over the pieces that were finally chosen. Each encounter, of course, was very different, and sometimes there was virtually nothing to say but a heartfelt thank you (Riptide has a firm policy of paying its contributors, though the cheque can be little more than a token). But I particularly loved working with those writers who were open to any suggestion I might have and willing to negotiate. It is a totally different experience to editing one’s own work (where there is inevitably a great plank in the eye); other people are much more clear-cut. I’m sure I’ve learned a huge amount from these exchanges and am grateful for those writers here who were patient and responsive to that (not quite as bad as letting a novice surgeon loose on your heart – but not so far off…).

Reading with a view to editing is different too from reading for pleasure. There is a responsibility attached to it: the responsibility to attempt to be less partial than you might otherwise be. You are not, for instance, furnishing your own home. Although it would be facile to claim that an editor is impartial (that isn’t the point, after all), I tried to read and to listen with an open mind and not just to respond to those stories or writers who would fit in with my own colour scheme. I hope that this is evident in the great variety of voices that eventually made their way to Volume 5: Ginny Baily, Sally Flint, Luke Kennard, Eleanor Knight, Jo Lloyd, Alison MacLeod, Adam Marek, Alison Napier, Jenny Newman, Wena Poon, Jane Rogers, Nicholas Royle, Jane Rusbridge, Robert Shearman, Karen Stevens, Zoe Teale and Matt Thorne.

There is a responsibility attached to it: the responsibility to attempt to be less partial than you might otherwise be. You are not, for instance, furnishing your own home. Although it would be facile to claim that an editor is impartial (that isn’t the point, after all), I tried to read and to listen with an open mind and not just to respond to those stories or writers who would fit in with my own colour scheme. I hope that this is evident in the great variety of voices that eventually made their way to Volume 5: Ginny Baily, Sally Flint, Luke Kennard, Eleanor Knight, Jo Lloyd, Alison MacLeod, Adam Marek, Alison Napier, Jenny Newman, Wena Poon, Jane Rogers, Nicholas Royle, Jane Rusbridge, Robert Shearman, Karen Stevens, Zoe Teale and Matt Thorne.

On the other hand, one of the unexpected joys of putting these stories together – shuffling them, typesetting them – was watching how, from such a diversity, connections began to form between them. I hadn’t set out to find a theme – my intention was only to find stories that grabbed and surprised me – so it was as if by magic that a theme began to emerge:

Flight – in terms of aeroplanes, in terms of fancy, in terms of evasion – as if the stories themselves had found a way of communicating with each other. And to put a seal on it, I got Matt Thomas, who had produced artwork for Volume 4, to come up with a suitable cover: his birds are stacked and ready for release (copies available from Amazon and directly from Riptide itself), vacating the same boxes that in turn will provide a resting place for the next in-flight of manuscripts.

We had a great launch of the magazine in Exeter, when Robert Shearman, Ginny, Sally and Alison Napier read extracts from their stories. A week later, Adam Marek read ‘Dinner of the Dead Alumni’ to a hugely appreciative crowd at the Lancaster Literary Festival. If you haven’t already bagged your copy, then I urge you to do so now, while they are still relatively tame and easy to catch…