Photo by Dave Earnshaw

The Illusion of the Final Version

by Will Bowerman

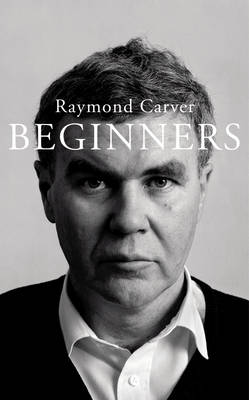

The reputation of Raymond Carver as a short story writer of the highest order is without question. His stories and the style he incorporates into his writing have infused writers, imitators, teachers, theorists and classes and will continue to do so. What is in question, however, is whether we wish to alleviate ourselves of the Carver we have come to experience and identify for the unknown Carver: the writer hunting his stories, refining his language, determining his route through the drafting process before the stories experienced the mind and pen of his editor, Gordon Lish.

Beginners (Vintage, 2010) offers a unique insight into the unedited version of what would become What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (Knopf, 1981), but is this ‘unique insight’ warranted? As completists, we search for and examine the minutiae of unwanted letters. We are dissatisfied with the final offering, longing for insight into the creative process – the hidden theories, the discarded versions, the door through which we can enter every discernible version of the author’s creation and our own critical, emotional and physical reactions to it.

The great unfinished works provide infinite ideas for how best to realise the originator’s vision. Who was closest – physically or intellectually – to the creator? Who can unlock the secrets and fill in the missing pieces? Beginners was published in hardback shortly before Nabokov’s The Original of Laura (Dying is Fun) (2009). Both arrived, deservedly, as literary events. In 2011, we will see the publication of the late David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King, a novel which was already years in formulation at the time of the author’s death, and hundreds of thousands of words in development. Yet it’s been claimed that the novel is a work in progress with only one-third of the project completed.

Whether or not the illusion of the final version is lost forever can only be disputed if these works are ignored. The value of Nabokov’s final writings was not to be debated; it was the unknown quality of the work in progress and whether we would ever be permitted to judge that quality for ourselves that was in question. If, as Nabokov requested, the manuscript had been burned after his death we would have been denied the opportunity see the great writer at work. Once The Original of Laura (Dying is Fun) was published, the sense of incompleteness resonated not just throughout the novel but also through every reader. In the case of Wallace, the sheer expanse of the work in progress will not allow, supposedly, for a full and comprehensive first edition. What has been excluded from his writings, to provide us with a realised narrative and satisfaction with what we have been offered, we may never know. Pages may remain hidden in a safe, or burned, or as Mark Twain declared before the publication of his letters this year, forbidden to be read until one hundred years after the author’s death.

With Beginners, Carver’s own creative process was more fully developed and this book represents the manuscript which he delivered to Lish before more than half of it was subsequently edited out for publication under the new Lish-determined title of What We Talk About When We Talk About Love – a line created by Carver’s pen. Lish changed titles, endings, character names and deleted whole passages and scenes. He transmuted Carver’s tone, style and narrative voice into the Carver we have come to know. It is no wonder that Carver’s reaction came in equal parts of celebration and horror. Beginners marks the restoration of Carver’s authentic voice, for better or worse. Here, the reader is allowed to decide for themselves: is it better to decipher the author’s constructions, or to sit back and marvel at their inconceivable wonder in the ‘finalised’ version?

With Beginners, Carver’s own creative process was more fully developed and this book represents the manuscript which he delivered to Lish before more than half of it was subsequently edited out for publication under the new Lish-determined title of What We Talk About When We Talk About Love – a line created by Carver’s pen. Lish changed titles, endings, character names and deleted whole passages and scenes. He transmuted Carver’s tone, style and narrative voice into the Carver we have come to know. It is no wonder that Carver’s reaction came in equal parts of celebration and horror. Beginners marks the restoration of Carver’s authentic voice, for better or worse. Here, the reader is allowed to decide for themselves: is it better to decipher the author’s constructions, or to sit back and marvel at their inconceivable wonder in the ‘finalised’ version?

The first story in both collections is ‘Why Don’t You Dance?’ A comparative reading between the two offers examples of Carver’s writing and Lish’s editorial decisions. It is clear that Carver’s version provides a more sentimental tone than that edited by Lish’s pen. Whilst Carver chose to name just one of the three characters in the story, Lish elects to do away with that name too, simply referring to this character as ‘the man’. The two other main characters (‘he’ and ‘she’) become ‘the boy’ and ‘the girl.’ Carver offers little detail about the characters other than their ages, but Lish omits even this in his edited version. The story becomes one entirely of event, and what we learn of the three people in it comes from action and dialogue. Lish alters the narrative from past tense to present early on in the story, which, alongside the cuts he makes, quickens the pace and affords the story a more active tone. The addition of harsher language, and the stripping back of repetition and longer sentences helped to establish Carver’s reputation as a Minimalist – a term he found disagreeable. The most controversial discovery, however, when comparing the two versions, is the addition of original text penned by the editor. While this text is inspired by Carver’s version, it represents more than cutting, editing or offering suggestions, as it alters the pace, style, tone and voice of the authorial draft. It is these moments which open the door to the controversy that Lish originated more of the Carver style than the author himself.

On August 11, 1982, Carver wrote a letter to Lish concerning the stories for a new book. ‘The stories in this new collection,’ he wrote, ‘are going to be fuller than the ones in the earlier books. And this, for Christ’s sake, is to the good. I’m not the same writer I used to be. But I know there are going to be stories in these 14 or 15 I give you that you’re going to draw back from, that aren’t going to fit anyone’s notion of what a Carver story ought to be – yours, mine, the reading public at large, the critics. But I’m not them, I’m not us, I’m me…I can’t undergo the kind of surgical amputation and transplant that might make them someway fit into the carton so the lid will close.’ Lish provided what he considered to be the barest minimum of cuts he could afford the writer, but it was to be the end of their working relationship.

The value for the literary theorist or creative writer of reading these stories side by side is clear – how far was the original voice altered by another, and to what purpose? Carver initially wrote to Lish after reading the edited version, to state that, ‘if the book were to be published as it is in its present edited form, I may never write another story.’ Soon after he changed his mind and became more supportive of its impending publication, but it is clear at least, that Carver’s voice had been dramatically altered by his editor. The book launched Carver into literary royalty and a thousand imitators would follow. It was also the last time Carver would work with Lish on a collection, preferring to publish Cathedral and Elephant under his own editorial guidance. It is not so much which version is better that deserves attention as it is what each version has to offer the reader. What We Talk About When We Talk About Love and Beginners appear as twins separated at birth. Having come together to search the differences between them, they learn more about each other and themselves in the process. The publication of Beginners provides us, as writers, with the opportunity to investigate the creative process at its highest order, to recognise that there is only the illusion of a final version and, most comfortingly, to realise that even the very best do not always get it right the first time.