photo © Peter Kirkeskov Rasmussen, 2013

*

Written for the THRESHOLDS International Feature Writing Competition last year, Stephen Devereux’s shortlisted essay asked the question: ‘Where are you Helen Harris?’ In this engaging piece, Stephen wrote about Harris’ short story ‘The Man Who Kept the Sweet Shop’, found in The Penguin Book of Modern Women’s Short Stories, yet he was unable to find more information about the author.

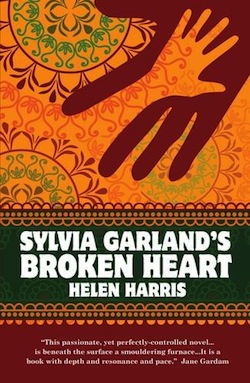

Now, in a follow-up special, Stephen interviews the elusive author – about her writing processes, choice of narrative perspective, and teaching creative writing – just after the publication of her fifth novel, Sylvia Garland’s Broken Heart.

~

An extract from ‘Where are you Helen Harris?‘

I’ll begin again with what is in the story. At its heart is a group of school girls. […] In this story, it is the group as a group that is the subject of the story. When we are given a little bit of information about one of them, she is viewed from the perspective of the group. We are told nothing about their home lives and not much more about their school lives. For most of the story they are either at the bus stop or on the bus.

The opening sentence – ‘The man who kept the sweet shop at the bus station was disappointing, years afterwards’ – makes it clear that it is the difference between what the girls were and what they have become that is the focus of the story. And what they remember (what most of us remember) is the time they were together as a group beyond the control of teachers and parents…

~

INTERVIEW WITH HELEN HARRIS

Stephen Devereux: Where did the inspiration come from for ‘The Man Who Kept the Sweet Shop’? Was there a biographical element or was it entirely imagined?

Stephen Devereux: Where did the inspiration come from for ‘The Man Who Kept the Sweet Shop’? Was there a biographical element or was it entirely imagined?

Helen Harris: The inspiration came from a real bus journey, a real bus station and a real sweet shop man. I grew up in Oxford and the old Gloucester Green bus station was a dingy, scuffed, second-rate sort of place. The sweet shop was, I think, in a portakabin. The characteristics of the sweet shop man and of the schoolgirls are imaginary. Today the bus station has been rebuilt and transformed. You could not possibly write fiction about it now. But the old bus station seemed to me – I think – to epitomise everything that was provincial, small town and second rate and I was at an age when one dreams of escaping. What the schoolgirls find unbearable in adulthood is that even though they have got away, the backdrop of their adolescence has stayed unchanged “denying all progress”.

SD: When researching your story for my essay, I could find no story that was similar to it. I felt the closest was Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener, with its central character who remains entirely unknown to the reader. When you began writing the story, was it your intention to write it without a central character? Did you consider it an innovative approach, or was this simply how the story needed to be told?

HH: I wanted to write about a place, an experience and a stage of life, not any particular person going through it.

As for your comments about how innovative you found the story to be, I think the explanation may be this: I was very young, I did not study English literature, either at A-level or at university, I was probably pretty ignorant and simply did not know what the conventions were.

SD: How do you begin writing a short story? Does it begin with a character, a plot, the opening sentence or a single image?

HH: My stories usually begin with a single sentence that contains an idea.

SD: What was the process through which the story was selected for The Penguin Book of Women’s Short Stories?

HH: The story first appeared in an Arts Council anthology in 1980: New Stories 5. It was reprinted in a second anthology, The Parchment Moon (Michael Joseph, 1990), and that anthology was republished as The Penguin Book of Modern Women’s Short Stories in 1991.

SD: There is a remarkable vividness about the story. How did you achieve this?

HH: I recreated the place and the feelings in my mind. I was still close to them.

SD: Whenever I have read the story with A-level students they have always responded to it enthusiastically. Why do you think it is so well received?

HH: I think A-level students are just the right age for this story. It is their own experience and they recognise what I describe wherever they are growing up.

SD: Given today’s concerns about safeguarding, do you think it would still be possible to write a story about a group of school-girls’ obsessive interest in such an apparently dubious individual?

HH: Don’t you think that today’s concerns about safeguarding have been more successful in developing a new vocabulary than in actually keeping children safe? (Similarly with inclusivity and diversity.) Officialdom considers its job done once the new words are created to define a problem, but on the ground not much changes. Having said that, in the 1970s and 80s people accepted as inevitable behaviour (such as Jimmy Savile’s) things which would – one hopes – not be tolerated today.

SD: Your novel Sylvia Garland’s Broken Heart came out in November, from Halban Publishers. Does the subject of your novel continue the theme of teenage years?

SD: Your novel Sylvia Garland’s Broken Heart came out in November, from Halban Publishers. Does the subject of your novel continue the theme of teenage years?

HH: No, Sylvia Garland’s Broken Heart is about a different phase of life completely: it is about a grandmother’s bond with her grandson and her predicament when his parents split up (among other things, of course).

SD: How would you say the novel and the short story differ? Is it merely a matter of length or are there structural differences?

HH: Your question would require another essay in response. Let me simply say that in a novel you have more room. Things can go wrong, you can digress, a few pages can be less good and the reader will still forgive you. In a short story, you have no leeway.

SD: How does the actual writing of a novel compare with the short story process?

HH: Again, it would need a volume to answer this question adequately. Zola described writing a novel as ‘un travail de cheminot’ – ‘a navvy’s job’ – and that is true. It is a long, hard slog, which you work away at for years. Writing a short story is a more delicate, fiddly task, maybe comparable to the work of a watchmaker or some other craftsman.

SD: When teaching, do you use examples from your own work?

HH: Yes, I do sometimes use my own work when teaching creative writing. There are certain explanations of the genesis and development of a story which you can only give if you wrote it yourself.

SD: How many other short stories have you written?

HH: About thirty.

SD: Do you encourage students to write short stories, or is your teaching more focused on the novel form?

HH: I teach a creative writing module at Birkbeck that runs for one academic year and the students need to submit three pieces of coursework. Because of these constraints, it makes sense to focus on the short story. Some of my students choose to work on longer pieces of fiction, but the majority enjoy the sensation of actually finishing something.

SD: Short stories seem to struggle to sustain a hold on the reading public when compared to the novel. Why do you think this is?

HH: I suppose it is the disruption of the repeated endings and beginnings, the change of voice and pace which puts many readers off collections of short stories. They can’t snuggle down and get immersed in them the way one can in a continuous narrative.

~

Thank you, Helen, for your enlightening answers and good luck with the new novel.

~

With thanks to Halban Publishers.