photo by L.L. Murray

by Mike Smith

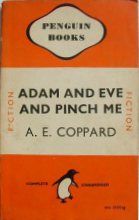

A.E. Coppard is one of the great, but largely overlooked, English short story writers. His story ‘Weep Not My Wanton’, was included in his first collection, Adam & Eve & Pinch Me, published in 1921. The story is relatively short, but by a close study of it we can learn a lot about the writing of characters.

There are other figures in this landscape, too. In the opening paragraph we are shown ‘two brown lads and a gypsy’ engaged in gelding young boars. These characters are only sparsely sketched, but as we will see, they contribute to what we experience and understand of the family, father and boy in particular.

At first sight, the story seems to be about the boy’s endurance, suffering the rebukes and blows of his father as he keeps the sixpence safe for his mother, but as I moved away from my first reading, it was the image of the father that stuck in my mind. Despite his drunken brutality he remains for me a figure of tragedy, rather than of villainy.

Coppard is meticulous in his presentation of this figure. When we first encounter him, he is simply ‘a labourer’ with his family, but as the little group approach we hear ‘the voice of the man’ which, a sentence later, is refined to ‘the voice of a man upbraiding his little son’.

Coppard is meticulous in his presentation of this figure. When we first encounter him, he is simply ‘a labourer’ with his family, but as the little group approach we hear ‘the voice of the man’ which, a sentence later, is refined to ‘the voice of a man upbraiding his little son’.

Here, Coppard’s choice of a single word is as important as his sentences. The change from the man to a man demands a subtle shift in our understanding. By changing the article, the father is elevated from an individual to representative of his sex. The introduction of the ‘little son’ also adds to our picture of the man, as does his manner of speech: ‘You’re a naughty, naughty – you’re a vurry, vurry naughty boy! Oi can’t think what’s comen tyeh!’

Coppard catches the accent and tone, and so do we. The repetitions and the use of italic on the second ‘vurry’ add emphasis and identity to the character’s voice.

The next sentence gives us an image to go with the sound: ‘The father towered above the tiny figure’. Note that the boy is now ‘tiny’, not merely ‘little’ and consider how the deeper meaning of the description would be affected had the two adjectives been reversed. The word ‘tiny’ would not have implied the weakness of the original description, and ‘little’, following it, would have lessened rather than increased the sense of the boy’s smallness. James Joyce’s call for the ‘right words in the right order’ springs to mind. Another quality of the father emerges in this sentence when we are told that he ‘kept his eyes stupidly fixed’ upon the boy. Again, a carefully selected attribute pinned to the character of the father.

As these two characters are presented together, we see and respond to them in tandem. After the description of the father, we are given a whole row of attributes of the child. He is ‘thin’, ‘spare’, ‘very shrunken’, and aged ‘seven or eight years’. This vulnerable appearance is reinforced when we are told that the boy ‘let no grief out of his lips, but his white face was streaming with dirty tears.’ Then we see his clothing, four items which in a sense do not belong to him: a ‘man’s coat’, an ‘unclean sailor jacket’, ‘women’s button boots’, and his ‘large knickerbockers’ which are too big for his ‘lean joints’. It is as if the boy is disguised by his apparel.

The man goes on ranting through the next paragraph, and it is here that he strikes the boy ‘with shock enough to disturb a heifer’, encouraged by the gypsy to ‘wallop his trousers!’ This, we are told, ‘the man ignored’. He ignores too, the noisy cries of the pigs and ‘the voice of the lark rioting above them all’. It’s a curious setting which the author wants us to notice, for the lark does not sing, it riots. These details, too, add to our picture of the man.

In the next paragraph we are introduced to the man’s wife and daughter: ‘The woman, a poor slip of a woman she was, walked behind them with a smaller child.’ We are told that she ‘seems’ to have ‘no desire to shield the boy or to placate the man’, a description which isn’t going to help the reader warm to her! We should know by now, though, that Coppard chooses his words with care. That ‘seems’, for example. The description of the woman is filled out very briefly and we are shown that she ‘gabbled’ to the ‘toddling babe’. Then we are cast back with the man who dominates this story.

The father’s appearance is presented in a series of adjective-noun combinations: ‘great figure’, ‘bronzed face’, ‘free and massive hand’. His dress is reduced to ‘trousers tied at the knee’, and a ‘wicker bag slung over his shoulder’. Coppard also tells us that he is ‘slightly drunk’, and describes at some length his odd way of walking – ‘lifting his heel higher than was required’, with ‘his foot firmly but obliquely inwards’.

At the heart of the story, buried, rather than highlighted amid descriptions of the father, we are told that he wears ‘two bright medals on the breast of his waistcoat, presumably for valour’. The mention of the medals is the only reference we are given to the character’s past, and it tells us that the man has been ‘presumably’ something other than what he is now – a drunken and abusive boor.

This paragraph moves from simple description to something deeper, something that we need to interpret to be able tounderstand. Why does the man walk the way he does? And why does the author, when presenting the medals, tell us they were awarded ‘presumably for valour’? This is the narrator turning to us and making a comment, not merely telling us what he sees, but questioning its significance, as if the narrator did not know for sure, as if the character were a real person rather than a mere construction of words. The complications multiply. The man is ‘oddly unprofane’, and this ‘gave a subtle and mean point to his decline from the heroic standard’. Here, that contextualisation has passed out of the landscape of the story and into our own world and we must ask what point; which ‘heroic standard’? Questions about the deeper meaning of the character, and of the story, are thrown at us without any certain answer. At the end of the paragraph we come back to the story’s normality and see the man as he gazes ‘swayingly at the boy’ before striking him. The boy takes the punishment, ‘crying quietly’ without trying to ‘avoid or resist’ his father.

When the man rebukes his son again, the father becomes an oppressive force within the story and we sense the unending

horror of the boy’s existence. At this point, we are reminded of the other characters. The baby daughter gives ‘gusts of laughter’ as the man seizes and shakes the boy, and the mother ‘coo[s] playfully at her’. This seemingly bizarre response is another part of the contextualisation of these characters. Coppard is showing us that the behaviour we’re witnessing is such a part of the family’s normal routine that it goes unnoticed by the mother.

horror of the boy’s existence. At this point, we are reminded of the other characters. The baby daughter gives ‘gusts of laughter’ as the man seizes and shakes the boy, and the mother ‘coo[s] playfully at her’. This seemingly bizarre response is another part of the contextualisation of these characters. Coppard is showing us that the behaviour we’re witnessing is such a part of the family’s normal routine that it goes unnoticed by the mother.

Slipping behind a hedge, the mother leaves the girl to her husband’s care. When she returns, the man walks on with his daughter and she sees the injuries he has inflicted on their son. It’s her longest speech: ‘“O, my Christ, Johnny!” she said, putting her arms round the boy, “what’s ’e bin doin’ to yeh? Yer face is all blood!”’

Johnny shrugs off his mother’s concerns and passes her the sixpence he has been hiding. The shock of this on the first reading, the poignancy of it on subsequent ones, is powerful, but it is not the end of the story. Though this scene is an epiphany, it is not the epiphany. Coppard could have left the story here, but he goes on to leave us with other images: the inn with ‘already a light in its window’; the ‘young pigs, bloody and subdued’, the ‘anxious farmer’, and above all, the closing image of ‘dimly’ heard ‘men’s voices and the rattle of their gear’.

The story raises a number of questions about how we create and present characters – about how deeply we go into them, about whether we see them from the inside, or the outside; about whether we explain why they are the way they are or leave them unexplained.

We only learn the names of the characters when the woman calls to ‘George’, and asks him to ‘look after Annie’. It is she, not the father and not the narrator, who calls the boy ‘Johnny’. Likewise, the sex of the younger child is not revealed until just before this point. Until then, she is referred to only as ‘the smaller child’ and ‘the toddling babe’. This, however, is all we need to know about the child until we are called upon to imagine her again. What we are told, though, reveals the character of the mother, and adds to our growing picture of the father.

When the man speaks to child we now know to be his daughter, we hear a distinct difference from the way he speaks to his son: ‘Carm on, me beauty!’ he says to her as he lifts the little girl to his shoulder. In the next line, we hear both tones of voice: ‘He’s a bad, bad boy; you ‘ave a ride on your daddy.’

We learn about these characters not only by what Coppard tells us about them, but also by the way they respond to each other. He makes no attempt to show us what is going on inside their minds, telling us only what they do and what they say. We must draw our own conclusions about what they think and feel. This is our contribution to the narrative. If Coppard had told us what the characters were thinking, we would be locked out of the story. This way we are brought closer to it.

We learn about these characters not only by what Coppard tells us about them, but also by the way they respond to each other. He makes no attempt to show us what is going on inside their minds, telling us only what they do and what they say. We must draw our own conclusions about what they think and feel. This is our contribution to the narrative. If Coppard had told us what the characters were thinking, we would be locked out of the story. This way we are brought closer to it.

It is in fact easy to imagine what a character like Annie might be thinking – very little, because she is so young. And it’s not difficult to work out a plausible mindset for the boy, who suffers now to save his mother from worse suffering later by preventing his father from reaching the inn with money to spend on drink. It is less easy to be sure about the woman. Does she know that the boy is hiding the tanner? We are not told that she is surprised to receive it, and this would explain her ‘seeming’ not to want to shield the boy from her husband’s anger. She is aware of her son’s sacrifice, and has no alternative but to allow it.

The father, though, is the one about whom we must really speculate. The ‘slightly drunk’, ‘oddly unprofane’ medal winner, ‘presumably’ once valiant, who has suffered a ‘decline from the heroic standard’, and ‘ignored’ the gypsy, and the ‘yell of the pig’ and ‘the lark rioting’. He is the enigma, yet he is the character that Coppard has devoted most words to, the one that we see and hear most clearly. Yet, he is the one I struggle most to understand, to interpret.

Looking back to the beginning, we see how Coppard creates an image of the land as ‘soft as ointment and sweet as milk’, and then immediately challenges this image as a ‘notion’ in the mind of ‘some happy victim of romance’. This is a land of oh so poetically evoked ‘slopes of barley’ where ‘the fogs of June being born in the standing grass beyond’ move ‘with the slow movement of summer sea, reaching no harbour, having no end’. In the final paragraph, we see the labourer and his family still moving towards the inn. They have themselves reached no harbour and at the close we sense that they are destined to remain adrift upon this sea, a vast sea that has ‘no end’.

.

Excellent article. I love how you break the story down to show how each word reflects character and contributes to the story’s overall meaning. I’m beginning to see that I have a tendency to dump information into my stories rather than creating pictures in the mind of a reader. Or at the very least, stop there without going forward. I think this is what separates those pieces that work versus those that fall flat on the page. A story also needs time to simmer before the images comes together, another great misconception of mine.